by NEIL SINYARD

“Over the years Frears has refined a magical instinct for just how long we want to see a face and how long a scene needs to be. If he could bottle this instinct, it could be called “Essence of Moviemaking”.”- Pauline Kael1

Interviewer: “Would you say that your films show a concern for people living on society’s fringes?”

Stephen Frears: “It would never cross my mind, but now you come to mention it…”

The opening

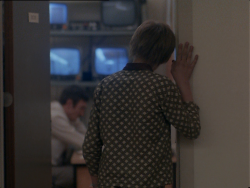

It is dead of night, and the sound of a crash is heard. Emerging out of the darkness, 11-year-old Leo (Richard Thomas) chances upon a scene of pure carnage, which, we will come to recognise, could stand as a symbolic representation of his vision of a broken-down grown-up world. A serious traffic accident has occurred, in which a lorry appears to have careered off a flyover and caused significant damage and serious injury below. The police, rescue workers and interested bystanders are already at the scene and getting in each other’s way. Amidst the chaos, no one pays much attention to the young boy moving between them or notice that Leo has spotted the cap of the chief inspector of police (Jack Douglas) on the back seat of his car and, while the inspector is otherwise occupied in trying to bring matters under control, has stolen it. When challenged about his presence on the scene, Leo has said he is on his way home; but, in fact, he pauses at the nearby police station and watches a young offender being roughly bundled out of a patrol car and taken inside. His curiosity being aroused, he stares in at the window as Inspector Ritchie (Derick O’Connor) is showing off the force’s new surveillance equipment. One of its monitors catches a glimpse of Leo.

It is dead of night, and the sound of a crash is heard. Emerging out of the darkness, 11-year-old Leo (Richard Thomas) chances upon a scene of pure carnage, which, we will come to recognise, could stand as a symbolic representation of his vision of a broken-down grown-up world. A serious traffic accident has occurred, in which a lorry appears to have careered off a flyover and caused significant damage and serious injury below. The police, rescue workers and interested bystanders are already at the scene and getting in each other’s way. Amidst the chaos, no one pays much attention to the young boy moving between them or notice that Leo has spotted the cap of the chief inspector of police (Jack Douglas) on the back seat of his car and, while the inspector is otherwise occupied in trying to bring matters under control, has stolen it. When challenged about his presence on the scene, Leo has said he is on his way home; but, in fact, he pauses at the nearby police station and watches a young offender being roughly bundled out of a patrol car and taken inside. His curiosity being aroused, he stares in at the window as Inspector Ritchie (Derick O’Connor) is showing off the force’s new surveillance equipment. One of its monitors catches a glimpse of Leo.

This opening is as striking for its style as its content. Although photographed by Chris Menges, who was the chief cameraman on Kes (1969), one could not mistake Bloody Kids for a Tony Garnett/Ken Loach social drama, for its look is lurid and garish and seems to be pushing the film beyond gritty realism. Stephen Frears was always looking for material that offered imaginative responses to the everyday, thus giving an overworked theme (in this case, juvenile delinquency) a fresh perspective and dimension. Visually Bloody Kids has something of the ambience of modern film noir, which will resurface in some of Frears’ later work, such as The Grifters (1990) and Dirty Pretty Things (2002). Some of his thematic preoccupations (to be discussed later) are being foreshadowed here also.

As Leo looks through the police station window, is he already formulating a plan in his own mind to learn more about the workings of the police by setting up a case of his own for them to solve? It will involve the theft of one of the blood bags being stored for the school play in his school’s refrigerator, and the collaboration of his easily manipulated best friend at school, Mike (Peter Clark). But the plan will go awry. Staging a fight using the fake blood outside a football ground, Leo is accidentally stabbed for real by Mike, who will go on the run, while Leo in hospital will concoct ever more fantastical tales to the police about what has happened and about the violent nature of his friend.

The making and reception of the film

Originally entitled Red Saturday and then One Joke Too Many and based on an original idea and screenplay by a rapidly rising star of theatre and television drama, Stephen Poliakoff, Bloody Kids was acquired for production by Barry Hanson and developed as a film for television. At that time Frears had only one feature film to his name, the unusual private-eye parody, Gumshoe (1971), but over the decade he had built up a formidable reputation as a director of television plays, particularly those in which he had collaborated with writer Alan Bennett and some of which had been produced by Hanson. Bloody Kids was filmed on location at Southend-on-Sea and at the Hampstead Royal Free Hospital in London. The two boys had never acted before. Their fake fight, which kicks off the whole drama, was filmed on a cold and windy morning outside the Southend football ground before an actual match. They were still filming when the crowd came out after the game and started gathering around the incident out of curiosity, which added a touch of authenticity. “We hadn’t planned to film the scene with a genuine crowd,” said Frears, “they were an unexpected bonus.” Frears was to become very adept at using unexpected situations to a film’s advantage. What realism taught him, he said, was “making the best use of where you are,” citing an occasion when the location prompted him on the spur of the moment to change the season in the script he was doing (The Hit) from Spring to Autumn. When the writer objected, Frears replied: “I just don’t have time to sew leaves on the trees.” When a giant crane was mistakenly delivered for a day when they were filming My Beautiful Laundrette (1985), Frears took the opportunity to create the most spectacular shot of the entire film, where the camera cranes from the launderette up and over the roof to disclose the gang of white youths readying themselves for violence.

Originally entitled Red Saturday and then One Joke Too Many and based on an original idea and screenplay by a rapidly rising star of theatre and television drama, Stephen Poliakoff, Bloody Kids was acquired for production by Barry Hanson and developed as a film for television. At that time Frears had only one feature film to his name, the unusual private-eye parody, Gumshoe (1971), but over the decade he had built up a formidable reputation as a director of television plays, particularly those in which he had collaborated with writer Alan Bennett and some of which had been produced by Hanson. Bloody Kids was filmed on location at Southend-on-Sea and at the Hampstead Royal Free Hospital in London. The two boys had never acted before. Their fake fight, which kicks off the whole drama, was filmed on a cold and windy morning outside the Southend football ground before an actual match. They were still filming when the crowd came out after the game and started gathering around the incident out of curiosity, which added a touch of authenticity. “We hadn’t planned to film the scene with a genuine crowd,” said Frears, “they were an unexpected bonus.” Frears was to become very adept at using unexpected situations to a film’s advantage. What realism taught him, he said, was “making the best use of where you are,” citing an occasion when the location prompted him on the spur of the moment to change the season in the script he was doing (The Hit) from Spring to Autumn. When the writer objected, Frears replied: “I just don’t have time to sew leaves on the trees.” When a giant crane was mistakenly delivered for a day when they were filming My Beautiful Laundrette (1985), Frears took the opportunity to create the most spectacular shot of the entire film, where the camera cranes from the launderette up and over the roof to disclose the gang of white youths readying themselves for violence.

Prior to its screening at 9.30 p.m. on Sunday 23 March 1980 on ITV, Bloody Kids was advertised on the front cover of that week’s edition of the TV Times under the heading: “The children beyond the law.”2 The magazine went on to describe the film as “dealing with the disturbing problem of children and crime, in a story of two 11-year-old boys who try to outwit the police. The story is fiction – but the problems it describes are only too painful fact. A glance at the newspaper headlines almost any day of the week makes one wonder whether we have created a generation of monsters.”3 This was somewhat at odds with how Poliakoff described the film in publicity notes provided for the press, in which he said simply: “The kids have been raised on TV images. They feel at home in their own dark exciting urban landscape and have learned to manipulate it for their own purposes.” Indeed, and perhaps inadvertently reflecting the material’s complexity, TV Times seemed to contradict itself in its further description of the film, in its listings referring to the boys’ actions not as a “crime” but as a “juvenile prank”.

“A generation of monsters”? Have “we” created them, as the magazine suggested? When reflecting on the film in the context of Poliakoff’s early writing career, the critic Robin Nelson claimed that “it is not always clear whether he [Poliakoff] attributes social failings to the individual youths or to the harsh environment which the economic and social structures afford them.”4 What is noticeable here, however, is the absence of parental control; a demoralized police force, where even the most sensitive of the policemen shown, PC Williams (Billy Colvill) can reflect that “it’s no job for a grown man”; a health service wilting under pressure, with a hospital lift out of order and its staff working to rule; a shabby environment with limited sources of diversion and entertainment; and a society that seems only capable of offering surveillance over stimulation.

“A generation of monsters”? Have “we” created them, as the magazine suggested? When reflecting on the film in the context of Poliakoff’s early writing career, the critic Robin Nelson claimed that “it is not always clear whether he [Poliakoff] attributes social failings to the individual youths or to the harsh environment which the economic and social structures afford them.”4 What is noticeable here, however, is the absence of parental control; a demoralized police force, where even the most sensitive of the policemen shown, PC Williams (Billy Colvill) can reflect that “it’s no job for a grown man”; a health service wilting under pressure, with a hospital lift out of order and its staff working to rule; a shabby environment with limited sources of diversion and entertainment; and a society that seems only capable of offering surveillance over stimulation.

After its television showing, the film began to create a stir on the international film festival circuit, particularly at the 1980 New York Festival, where it was shown as part of a strand entitled ‘British Film Now’. In a review in the New York Times, Janet Maslin wrote that it “gracefully and economically moves through a cool forbidding world of the urban young,” evoking a world of “deadened responses, bright neon colors, soulless activity.”5 She was particularly impressed by what she called the “the light, concise feeling” of Frears’ direction and “its lovely mode of punctuation as he fades swiftly and delicately out of one episode to the next.” In fact, it was Frears’ direction that particularly caught the eye of the New York critics more than the film’s depiction of modern Britain. Frears was to call himself a “rather odd combination of somebody enmeshed in British society but with a yen for American movies.”6 Perhaps because of this, American critics appeared to have no difficulty in attuning themselves to the film’s world; they probably saw some affinities with Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973).

The favorable reception given to the film on the festival circuit was undoubtedly instrumental behind the British Film Institute’s decision to give it a limited release on some of the UK’s regional cinema outlets in November 1982. By then, Stephen Poliakoff’s reputation had risen sharply because of his award-winning television play Caught on a Train (1980), so splendidly acted by Peggy Ashcroft and Michael Kitchen, and superbly directed by Peter Duffel. The UK cinema release of Bloody Kids also coincided with the launch on 2 November 1982 of the new television station Channel 4, part of whose remit was to fund and re-vitalize feature film making in Britain and to provide a significant emphasis to its representation of youth culture. Although not a Channel 4 film, Bloody Kids seemed in some ways a kind of standard bearer for the quality television film – fresh, challenging, unconventional – that the new channel aimed to provide. Frears had already been signed up to direct Channel 4’s first feature film showing on its opening night, Walter (1982), starring Ian McKellen; and he was to go on to direct what is arguably the finest of all Channel 4-funded films, My Beautiful Laundrette.

A joke too far

When Leo first outlines to Mike his plan of staging a fake fight between them, which will look sufficiently bloody and violent for the police to become involved, he concludes: “Then I’ll tell ‘em it was a joke.” Mike seems more puzzled than amused and asks: “Why are we doing this?” “Surprise ‘em, that’s why,” replies Leo; but it is unsettling that Mike is willing to go along with a plan he seems not to understand nor even fully approve. He is right to sense that there might be more to this than a simple joke at the expense of the police. It has already been suggested in the school scenes that Leo is a potential troublemaker and attention-seeker who is determined to make his mark. In fact, he has already literally done so when he defiantly draws a line across a wall in the school corridor with indelible pencil. Watching cops and robbers on television and being momentarily entangled in the police operation in the opening accident, he wants to participate in a drama of his own contriving. He will lead the police a merry dance and do so by implicating his friend in his stabbing and mischievously depicting him as an aggressive personality who has declared his intention to kill someone before his 12th birthday. A cold-blooded, manipulative streak in Leo is here finding a disturbing outlet.

When Leo first outlines to Mike his plan of staging a fake fight between them, which will look sufficiently bloody and violent for the police to become involved, he concludes: “Then I’ll tell ‘em it was a joke.” Mike seems more puzzled than amused and asks: “Why are we doing this?” “Surprise ‘em, that’s why,” replies Leo; but it is unsettling that Mike is willing to go along with a plan he seems not to understand nor even fully approve. He is right to sense that there might be more to this than a simple joke at the expense of the police. It has already been suggested in the school scenes that Leo is a potential troublemaker and attention-seeker who is determined to make his mark. In fact, he has already literally done so when he defiantly draws a line across a wall in the school corridor with indelible pencil. Watching cops and robbers on television and being momentarily entangled in the police operation in the opening accident, he wants to participate in a drama of his own contriving. He will lead the police a merry dance and do so by implicating his friend in his stabbing and mischievously depicting him as an aggressive personality who has declared his intention to kill someone before his 12th birthday. A cold-blooded, manipulative streak in Leo is here finding a disturbing outlet.

Poliakoff’s development of the events following the stabbing is quite ingenious. The narratives of Leo and Mike separate but are still interconnected, in that both now involve different levels of manipulation. Whilst Leo is spinning his tales in hospital to doctors, nurses, and the police, who are suspicious but not yet disinclined to believe him, Mike has been drawn into the clutches of a gang led by a sort of modern Artful Dodger, Ken (Gary Olson), who has taken the reluctant lad under his wing. He begins to initiate him in the arts of petty crime: how to steal a car; how to drive round a shopping mall precinct and evade police cameras; how to order a Chinese meal and then leave without paying. By this time Mike seems to be in a nightmare from which he cannot escape. Fearing retribution from the police, he tells Leo that “they’ve got to know it wasn’t real,” but now fantasy is racing ahead of fact, and the so-called ‘joke’ is being played out in deadly earnest and gathering momentum. When the two boys meet again, another fight breaks out between them but this time it is for real.

Poliakoff’s development of the events following the stabbing is quite ingenious. The narratives of Leo and Mike separate but are still interconnected, in that both now involve different levels of manipulation. Whilst Leo is spinning his tales in hospital to doctors, nurses, and the police, who are suspicious but not yet disinclined to believe him, Mike has been drawn into the clutches of a gang led by a sort of modern Artful Dodger, Ken (Gary Olson), who has taken the reluctant lad under his wing. He begins to initiate him in the arts of petty crime: how to steal a car; how to drive round a shopping mall precinct and evade police cameras; how to order a Chinese meal and then leave without paying. By this time Mike seems to be in a nightmare from which he cannot escape. Fearing retribution from the police, he tells Leo that “they’ve got to know it wasn’t real,” but now fantasy is racing ahead of fact, and the so-called ‘joke’ is being played out in deadly earnest and gathering momentum. When the two boys meet again, another fight breaks out between them but this time it is for real.

Frears as auteur

Bloody Kids is an exhilarating but edgy movie, zig-zagging its way through an unpredictable series of events, and with an abrasive and anarchic spirit that seems to derive in part from the temperament of its director. (When he was a castaway on Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs, Frears had chosen as his favourite disc the Groucho Marx song in Horse Feathers, ‘Whatever it is, I’m against it’.) I am aware that Frears would be resistant to this line of argument. In several interviews, he has indicated that he has no time for the auteur theory, that critical procedure which seeks to ascribe the core meaning (and quality) of a picture to its director. He has always insisted that he is a director for hire, moving freely between film and television, Hollywood and Britain, big-budget star vehicles to modest assignments outside of the mainstream, sometimes in the same year (for example, in 1992, where he went straight from the $42 million Dustin Hoffman blockbuster, Accidental Hero to the whimsical low-budget Roddy Doyle comedy, The Snapper). With Bloody Kids, he would have been quick to acknowledge the quality of his cast (which features fleeting appearances from such future formidable performers as George Costigan, Brenda Fricker, Geraldine James, Roger Lloyd-Pack and Mel Smith) and the important contributions of his technical team. If anything, rather than a directors’ cinema, Frears’ work, he would argue, seems to support the notion of a writers’ cinema, since he has collaborated with a stunning array of writers who comprise practically the cream of British screen and theatrical dramatists of the last half century: in addition to Poliakoff, his writing collaborators have included Alan Bennett, Steve Coogan, Roddy Doyle, Lee Hall, Christopher Hampton, David Hare, Hanif Kureishi, Jimmy McGovern and Peter Morgan. When asked once where he gets his inspiration, he answered: “Through the letter box.” Nevertheless, this begs the question of why certain stories seem to attract him more than others, generally those that, as Lesley Brill has astutely observed, “offer an unusual perspective on the familiar”, which in turn allows him to go beyond realism in finding a style to match his subject. Many of his films have female leads and, in fact, all the seven Oscar-nominated performances in his films have been by women, which might make Bloody Kids look somewhat atypical, since it has no major female roles. Yet, in another respect, the material seems prophetic.

Bloody Kids is an exhilarating but edgy movie, zig-zagging its way through an unpredictable series of events, and with an abrasive and anarchic spirit that seems to derive in part from the temperament of its director. (When he was a castaway on Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs, Frears had chosen as his favourite disc the Groucho Marx song in Horse Feathers, ‘Whatever it is, I’m against it’.) I am aware that Frears would be resistant to this line of argument. In several interviews, he has indicated that he has no time for the auteur theory, that critical procedure which seeks to ascribe the core meaning (and quality) of a picture to its director. He has always insisted that he is a director for hire, moving freely between film and television, Hollywood and Britain, big-budget star vehicles to modest assignments outside of the mainstream, sometimes in the same year (for example, in 1992, where he went straight from the $42 million Dustin Hoffman blockbuster, Accidental Hero to the whimsical low-budget Roddy Doyle comedy, The Snapper). With Bloody Kids, he would have been quick to acknowledge the quality of his cast (which features fleeting appearances from such future formidable performers as George Costigan, Brenda Fricker, Geraldine James, Roger Lloyd-Pack and Mel Smith) and the important contributions of his technical team. If anything, rather than a directors’ cinema, Frears’ work, he would argue, seems to support the notion of a writers’ cinema, since he has collaborated with a stunning array of writers who comprise practically the cream of British screen and theatrical dramatists of the last half century: in addition to Poliakoff, his writing collaborators have included Alan Bennett, Steve Coogan, Roddy Doyle, Lee Hall, Christopher Hampton, David Hare, Hanif Kureishi, Jimmy McGovern and Peter Morgan. When asked once where he gets his inspiration, he answered: “Through the letter box.” Nevertheless, this begs the question of why certain stories seem to attract him more than others, generally those that, as Lesley Brill has astutely observed, “offer an unusual perspective on the familiar”, which in turn allows him to go beyond realism in finding a style to match his subject. Many of his films have female leads and, in fact, all the seven Oscar-nominated performances in his films have been by women, which might make Bloody Kids look somewhat atypical, since it has no major female roles. Yet, in another respect, the material seems prophetic.

After the unexpected success and enthusiastic reception of My Beautiful Laundrette in America, he was offered the chance to direct the film version of Christopher Hampton’s stage success, Dangerous Liaisons (1988), based on the scandalous 18th century novel by Henri Laclos. Coincidentally, and fresh from his Oscar-winning triumph with Amadeus (1984), Milos Forman was making a film, Valmont (1989), on the same theme; and yet Forman’s interpretation was unexpectedly upstaged by the verve and panache of Frears’ version, which, as well as being a commercial hit, went on to win three Oscars and several Oscar nominations. “It’s a sort of incredible film,” Frears has said. “When I watch it, I can’t believe I directed it.” Yet if you watched it in conjunction with Bloody Kids, I think you could very much believe that Frears directed it: the films have the same kind of impudent humor, social satire, and a similar choreographic energy in the camera movement. Both films are lifted into the realms of dark melodrama by George Fenton’s dashing and rhythmically pulsating scores. In Dangerous Liaisons, the Marquise (Glenn Close), in her sexual dealings, describes herself as “a virtuoso of deception”; in his different context, Leo in Bloody Kids could claim the same for himself. And what is Bloody Kids but a story of a dangerous liaison?

In fact, it is possible to see dangerous liaisons as a recurrent pattern at the heart of Frears’ work. One thinks of the Pakistani Omar and his affair with the ex-National Front white schoolfriend Johnny in My Beautiful Laundrette, which will culminate in violence; the hit man and the gangster in The Hit (1984), making contact in the context of impending execution; Joe Orton and his gay lover in the biopic Prick Up Your Ears (1987), a relationship which will end in murder; mother, son and femme fatale in The Grifters, a lethal cocktail of deadly liaisons if ever there was one; the precarious friendship between two refugees in Dirty Pretty Things, which endangers both their lives; the friendship between a Queen and her Indian servant in Victoria and Abdul (2017), which scandalizes the royal household and has political repercussions. In this category, one might even slip in two television dramas about British politics, The Deal (2003), portending the future stormy relationship between Prime Minister, Tony Blair and his combative Chancellor, Gordon Brown; and A Very English Scandal (2018), where Liberal Party leader Jeremy Thorpe (Hugh Grant) resorts to desperate measures to rid himself of a former gay lover (Ben Whishaw) who could bring down his career. It has been said that Frears’ films have explored different varieties of love in an unconventional way, but I have always thought that his key films are more about friendship than love, but a particular kind of friendship that often develops into a power struggle in which one of the protagonists could become the nemesis of the other. It is the element of danger that gives the relationship its dramatic spice; and Bloody Kids is a forerunner of this.

In fact, it is possible to see dangerous liaisons as a recurrent pattern at the heart of Frears’ work. One thinks of the Pakistani Omar and his affair with the ex-National Front white schoolfriend Johnny in My Beautiful Laundrette, which will culminate in violence; the hit man and the gangster in The Hit (1984), making contact in the context of impending execution; Joe Orton and his gay lover in the biopic Prick Up Your Ears (1987), a relationship which will end in murder; mother, son and femme fatale in The Grifters, a lethal cocktail of deadly liaisons if ever there was one; the precarious friendship between two refugees in Dirty Pretty Things, which endangers both their lives; the friendship between a Queen and her Indian servant in Victoria and Abdul (2017), which scandalizes the royal household and has political repercussions. In this category, one might even slip in two television dramas about British politics, The Deal (2003), portending the future stormy relationship between Prime Minister, Tony Blair and his combative Chancellor, Gordon Brown; and A Very English Scandal (2018), where Liberal Party leader Jeremy Thorpe (Hugh Grant) resorts to desperate measures to rid himself of a former gay lover (Ben Whishaw) who could bring down his career. It has been said that Frears’ films have explored different varieties of love in an unconventional way, but I have always thought that his key films are more about friendship than love, but a particular kind of friendship that often develops into a power struggle in which one of the protagonists could become the nemesis of the other. It is the element of danger that gives the relationship its dramatic spice; and Bloody Kids is a forerunner of this.

Summing up

The ending is as remarkable as the opening. Leo has run amok, escaping from his hospital bed, and setting off a fire alarm that is prompting an emergency mass evacuation from the hospital. Whereas Mike is wanting the whole thing to stop, Leo insists that it is just starting. Their violent tussle in the lift is brought to a sudden halt when the lift reaches ground floor and the doors open onto a scene of chaos bordering on surrealism, as casualties, patients, doctors, nurses, policemen and fire fighters float past the boys’ field of vision towards the hospital exit in a sort of dream-like slow-motion. That extraordinary image alone could have inspired one of Frears’ directing mentors, Lindsay Anderson to make Britannia Hospital in two years’ time. It brought to my mind a line by the poet WH Auden in his ‘Address for a Prize Day’ in The Orators (1932): “What do you think about England, this country of ours where nobody is well?” The final shot is a freeze frame which shows our two underage kids in the act of naughtily smoking a cigarette as they leave the hospital to confront the adult world: but it also has the effect of ending the film on a disquieting question mark, rather like the famous freeze frame that concludes Francois Truffaut’s Les Quatre Cents Coups (1959). What will they do next? In the long term, where are they heading? “You’re gonna be quite famous,” Ken has said to Mike earlier in the evening during their Saturday night spree in Southend-on-Sea. “Infamous” might prove to be nearer the mark.

The ending is as remarkable as the opening. Leo has run amok, escaping from his hospital bed, and setting off a fire alarm that is prompting an emergency mass evacuation from the hospital. Whereas Mike is wanting the whole thing to stop, Leo insists that it is just starting. Their violent tussle in the lift is brought to a sudden halt when the lift reaches ground floor and the doors open onto a scene of chaos bordering on surrealism, as casualties, patients, doctors, nurses, policemen and fire fighters float past the boys’ field of vision towards the hospital exit in a sort of dream-like slow-motion. That extraordinary image alone could have inspired one of Frears’ directing mentors, Lindsay Anderson to make Britannia Hospital in two years’ time. It brought to my mind a line by the poet WH Auden in his ‘Address for a Prize Day’ in The Orators (1932): “What do you think about England, this country of ours where nobody is well?” The final shot is a freeze frame which shows our two underage kids in the act of naughtily smoking a cigarette as they leave the hospital to confront the adult world: but it also has the effect of ending the film on a disquieting question mark, rather like the famous freeze frame that concludes Francois Truffaut’s Les Quatre Cents Coups (1959). What will they do next? In the long term, where are they heading? “You’re gonna be quite famous,” Ken has said to Mike earlier in the evening during their Saturday night spree in Southend-on-Sea. “Infamous” might prove to be nearer the mark.

Sources consulted

Chris Allison, ‘Bloody Kids’, Screenonline, available here.

W H Auden, The English Auden: Poems, Essays and Dramatic Writings 1927-1939, edited by Edward Mandelson (Faber & Faber, 1977).

Lesley Brill, The Ironic Film Making of Stephen Frears (Bloomsbury, 2016).

Lester Friedman (ed.), Fires Were Started: British Cinema and Thatcherism (Wallflower Press, 2006). Second edition.

Pauline Kael, Hooked (Marion Boyars, 1990).

Robin Nelson, Stephen Poliakoff on Stage and Screen (Methuen, 2011).

Pauline Kael, review of My Beautiful Laundrette, New Yorker, in Pauline Kael, Hooked (Marion Boyars, 1990). ↩

TV Times, 22-28 March 1980, p. 1. ↩

Ibid., p. 2. ↩

Robin Nelson, Stephen Poliakoff on Stage and Screen (Methuen, 2011), p. 215. ↩

Janet Maslin, New York Times, 23 September 1980. ↩

Lesley Brill, The Ironic Film Making of Stephen Frears (Bloomsbury, 2016), p. 8. ↩