by NEIL SINYARD

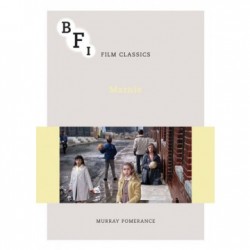

Book review: Murray Pomerance, BFI Film Classics: Marnie, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, 96 pp., £12.99

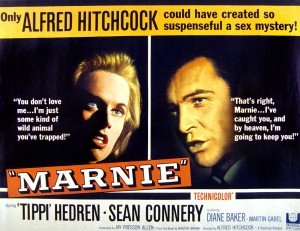

Fifty years after the film’s release, the jury is still out on Alfred Hitchcock’s 1964 suspense melodrama, Marnie. It was widely condemned and even derided on its first release for its apparent technical incompetence, artificial sets, and dubious sexual politics, though it found an eloquent early champion in Robin Wood, who proclaimed it a masterpiece in his trailblazing monograph, Hitchcock’s Films (1965) and thereafter never wavered in that opinion.1 More recent accounts include a thoughtful and sympathetic book by Tony Lee Moral about the film’s production (2002),2 and Donald Spoto’s latest, increasingly disillusioned volume on Hitchcock, Spellbound By Beauty (2009), where the film’s aesthetic quality takes second place to Spoto’s allegations about the director’s sexual harassment of his leading actress.3 Inspired by Spoto’s book, the tv movie, The Girl (2012) dramatised the relationship between Hitchcock and Tippi Hedren; and it prompted an article in The Guardian, which described Marnie as ‘a terrible movie and a cruel one: the idea that a woman sexually traumatised by her childhood can be saved by submitting to a controlling rapist, is offensive and plain wrong.’4 Yet might it not be the article, rather than the film, that is ‘offensive and plain wrong’? Reading it, one could almost hear Robin Wood turning in his grave.

In his stimulating new study of Marnie, Murray Pomerance, to his credit, does not spend time remonstrating with the film’s detractors, which could be a wearisome exercise; when he does quote a fellow critic, it is invariably in a positive spirit and with a view to augmenting his own argument. The film’s quality emerges quite naturally from his enthusiastic, intelligent and insightful commentary. He plunges the reader straight into the film’s opening (one of the cinema’s great opening sequences). The camera focuses on a bulging yellow handbag (already suggestive of money) being carried under her arm by a mysterious female whom the camera follows along a deserted train platform, then stops, then follows again briefly, then stops, as if exhausted by the pursuit: its quarry has escaped. As Pomerance emphasises, a dominant theme of the film is flight: at this stage from a crime (the heroine is quickly established as a thief); then from her surrounding stifling society (the following scene with the outraged employer from whom she has stolen suggests she may have been subjected to some form of sexual harassment); but crucially from herself and from her own identity. It is some time before we are allowed to see her face. It has been calculated that Tippi Hedren as Marnie has 32 costume changes in the film, which, as well as keeping Edith Head on her toes, is expressive not only of the character’s external fluidity of appearance but also of the internal fragility of her sense of self. Soon we are to become aware that she harbours secrets deeper than her criminal activities, or her dislike of men, or an unusually tense relationship with her mother. There is also an irrational fear of the colour red at moments of stress or distress, and nightmares triggered by storms that seem linked to some fearful event from her childhood. The film’s narrative trajectory is dedicated to closing off her successive retreat from these demons to the point when she must finally confront them: only then will she able to find herself.

When Mark Rutland (Sean Connery) comes onto the scene and falls in love with her, Marnie’s flight from self becomes increasingly difficult, particularly when he discovers her theft from his office and virtually blackmails her into marriage so as to escape prosecution or an inevitable later apprehension by a male victim who might be much less forgiving. Is Mark’s behaviour that of a ‘controlling rapist’ (to borrow the phrase in the Guardian article) or that of a potential saviour prepared to defy conventional morality to save the woman he has come to love? There have been many accounts of the central relationship in Marnie, and particularly of the motivation behind Rutland’s actions, but I know of none more sympathetically attuned to the tone of the film than the following account in Pomerance’s book:

Mark’s sole project in Marnie is to rescue this girl from her amnesia, help her locate the memories of ‘old times’ so she can live in the present. He must time-travel with no map. Clues not placed in the narrative so Mark can cut a path to Marnie’s rescue are there so that viewers can share willingly in his concern. We must come to love Marnie because of her blazing pride, her animality, the elemental warmth buried within the frozen sheath of her fear.5

One of the particular pleasures of the book is the attention to the numerous felicities and subtleties of vocal intonation and dialogue delivery of the two leading actors. It is refreshing to see Tippi Hedren’s performance so eloquently celebrated, when some of the mythology surrounding the film (partly encouraged by Hitchcock himself) has been the suggestion that Hedren was an inadequate substitute for Hitchcock’s preferred choice of Grace Kelly, who had regretfully decided that her royal responsibilities as Princess Grace of Monaco compelled her to decline the role. In fact, I have often wondered whether her eventual rejection of the part was her suspicion that it might be beyond her capabilities. She could certainly have conveyed Marnie’s frosty exterior, but could she have conveyed the vulnerability of a frightened child that Hedren so courageously and capably assays in the extraordinary revelation scene at the end, where the actress has to simulate the tormented state of mind of a five-year-old girl? I wonder.

With the aid of a detailed study of the film’s preparatory production notes, Pomerance has no difficulty in defending Hitchcock from the charges of technical sloppiness and demonstrating that the stylised artificial backdrops are part of the film’s aesthetic design. It is not as if Hitchcock has not done this sort of thing before. In the famous love scene in the hotel room in Vertigo, when James Stewart’s hero thinks he has brought his love-object (Kim Novak) back to life, Hitchcock has incorporated back projection of a livery stable from an earlier scene to suggest the depth of Stewart’s delusion, the sense that this re-creation of the past is a fantasy inside his own head. Hitchcock’s use of back projection during Marnie’s ride on her beloved horse, Forio has a similar expressive implication. The director wants simultaneously to convey both Marnie’s sense of release but also the sense that this is not a genuine release and that her feeling of freedom is illusory. As Pomerance points out, Tippi Hedren was an accomplished rider, so there would have been no need to use back projection unless it were at the service of some other expressive purpose.

The back-projection debate is familiar territory in Marnie criticism and can never be wholly conclusive (one can acknowledge the deliberate and valid intention behind Hitchcock’s aesthetic strategy without necessarily being convinced by the result). Less familiar in Marnie criticism is what the blurb at the back of the book describes as the author’s ‘sharp-eyed understanding of American society and mores’, which extends to a particularly illuminating discussion of the North/South divide in the film and even the symbolic significance of the pecan pie baked by Marnie’s mother.

There is also a particularly good analysis of the fox-hunting sequence, where he argues that Marnie’s trauma here is not simply due to the sudden sight of the colour red but also by what he calls her ‘profound identification with the victimised animal. All too plainly, Marnie can see how society is little more than a fox hunt, with the callous, brave, unforgiving, and desperate (Strutt and Co) ganging up on the weak, vulnerable, feelingful and innocent…. She is the fox, a race with the hounds behind.’6 That section of the text took me back to the film’s first scene after the opening, announced by Strutt’s ‘Robbed!’ and where, joined by Mark who is visiting the premises, Strutt (Martin Gabel) affirms his conviction that the robbery has been committed by his former employee Marion Holland (one of Marnie’s aliases). Simply the way he describes her to the police is very revealing about the male classification of women against which Marnie rebels. Strutt can describe her appearance and indeed measurements in great detail (the secretary’s reaction whilst he is doing so is a picture: she has clearly seen all this before). Mark also joins in with this callous classification, saying ‘Oh, that one’ and recalling her as ‘the brunette with the legs.’ Strutt particularly remembers her habit of ‘pulling her skirt down over her knees as if they were a national treasure’, and it is a gesture that will later give Marnie away when she comes to work at Rutland’s: Mark will remember Strutt’s description. What is being implied through all this is a motive behind Marnie’s kleptomania: namely, a form of revenge against the patriarchal world in which she lives and the sexist attitudes she has to endure. (Significantly, we will learn that she steals in order to win her mother’s love.) One of the most sympathetically observed themes in the film is that of the situation of the modern woman trying to operate in a man’s world and how difficult it is for someone like Marnie in this society to maintain her sexual and financial independence. It reminds me of that superb moment in Rear Window when Jeffries (James Stewart) is spying on Miss Torso in one of the apartments opposite as she entertains a number of gentleman acquaintances in what seems to be a formal cocktail party. Jeffries rather leeringly refers to her as a queen bee, but Lisa (Grace Kelly), a successful career woman, has a much clearer perception of the situation and puts Jeffries straight (and the animal imagery looks ahead to Marnie). ‘I’d say she’s doing a woman’s hardest job,’ she explains. ‘Juggling wolves’.

There is another key moment in Marnie where a comparison with Rear Window suggests itself, and it occurs in the revelation scene when Marnie finally recalls the incident in her childhood when she has killed the sailor. It is activated by her sight of a struggle between a white-shirted Mark and her mother, at which point the memory she has so long repressed takes over and is visually recalled. Pomerance valuably reminds us that Mark can see none of this recollection and ‘is experiencing a form of paralysis akin to what besets Jeff Jeffries in Rear Window when through his long focus lens he sees his beloved Lisa Fremont caught in a murderer’s grip and, hobbled in his wheelchair can do nothing to save her.’7 Similarly in Marnie: far from being controlling, Mark is at this key point in the story completely helpless. Pomerance describes this moment as ‘the paralysis of dramatic involvement’.8 I would take this further and suggest that it is the moment in both films when the hero is confronted with the full consequences of his obsession and where it has led; the perilous terrain into which his obsession might have plunged the person he most loves; and, perversely perhaps, the moment in the film more than any other when he recognises the intensity of that love.

Appropriately, the most contentious section of the book deals with the most contentious section of the film (it led to screenwriter Evan Hunter’s removal from the project): namely, the honeymoon sequence. Is the scene when Mark finally has intercourse with his wife a ‘rape’ scene? The screenwriter Evan Hunter thought it was, which is the reason he was removed. The new writer, Jay Presson Allen always thought the scene was dealing with a difficult marital situation, and the word ‘rape’ was never used in her discussions with Hitchcock. There is a lot of sensitive detail in Pomerance’s description of the whole sequence (the reference to Klimt is a particularly lovely observation), but there is also an element of tentativeness and imprecision not present elsewhere in the volume. ‘What precisely can Mark take her to mean when Marnie bellows “No!”?’ he asks.9 Well, precisely: ‘No’. It is difficult to see any ambiguity in Marnie’s response; the rejection could hardly be plainer. Pomerance posits the suggestion that Mark’s entry into her bedroom might have awakened another occasion in her past that she is trying to suppress rather than signifying a rejection of any form of sexual congress with Mark himself. He writes: ‘When Mark kissed her in his office during the thunderstorm, and again in the stables at Wykwyn, we saw her fondness for sex, at least with him.’10 Not exactly. In the scene in his office, Mark could be seen as taking advantage of Marnie’s obvious terror, certainly comforting her, but also using the opportunity to make a romantic advance. His line, ‘You’re safe… from the lightning’ has the undercurrent of ‘but not from me’. It always reminds me of that moment in Vertigo when Scottie is comforting a similarly distressed Madeleine, and says, ‘No one possesses you, you’re safe with me’, which, in the full context of the film, will become profoundly ironic. Similarly with the love scene in the stables: it concludes not happily, but with Marnie looking away from Mark and with an expression on her face of profound anxiety. Her robbery of Rutland’s safe directly follows that love scene in the stables and suggests a connection: the theft could almost be a kind of rebuke directed at Mark’s romantic presumption. It certainly indicates her intention to effect a closure of the relationship and her desire to flee from it.

In discussing the actual ‘rape’ scene, Pomerance quotes William Rothman to the effect that ‘we have grounds for believing, as Mark does, that he is making love to her, not raping her. As Hitchcock films this moment, she even seems to move on her own accord to the bed, though backward, as if in a trance.’11 This rather glides over the fact that Marnie is to follow this sexual experience with an immediate attempt at suicide. To compound the impression of authorial unease, there is an odd misprint hereabouts in the text (along with the erroneous dating of Winston Graham’s novel as 1971, not 1961, it is the only such instance I spotted) when Pomerance writes; ‘There is no escape from the fact that he [Mark] is become the camera.’ I presume what is meant is ‘has become’, because the author then quotes Raymond Bellour as saying that ‘Hitchcock becomes a sort of double of Mark’. He then concludes that, like Mark, ‘we are all now very much wanting to go to bed with Marnie’ and being held back.12 On the contrary, it is equally possible, and arguably more plausible (because of the suicide attempt that follows) that Hitchcock is inviting us to identify with Marnie rather than Mark at this stage – the close up of Mark at the moment of intercourse looks more threatening than seductive – and share her feelings of desolation. As I have argued elsewhere, the character of Marnie (her repression, the private fears beneath the external calm, the sublimation and displacement of her sexuality) seems much closer to that of Hitchcock’s own personality than does the virile, self-confident hero played by Sean Connery. Ironically, much earlier in his book, Pomerance has made a very similar observation when he has claimed: ‘If ever he [i.e. Hitchcock] had a female alter ego….Marnie is her epitome.’13 Absolutely: and it is curious that he does not follow through this intuition in the film’s most controversial scene, because it could illuminate and even validate Hitchcock’s whole presentation.

Even in a detailed and rigorous study such as this, one cannot expect complete comprehensiveness in coverage of such a complex film. However, I was a little surprised by two omissions. There is no extended discussion of what has always seemed to me the key scene in the film: the ‘free association’ scene between Marnie and Mark, which brings together all the main elements of Marnie’s trauma; is the scene when she openly challenges Mark in suggesting that his obsession might be as ‘sick’ as her repression; where, for the first time, she is driven to concede that she needs and wants help; and where Mark’s genuine love for her is apparent in his gesture of protectiveness and concern. Hedren, Connery and Hitchcock are at their very best here. ‘It’s a very sad scene, isn’t it?’ Hedren said to Hitchcock at one of their script sessions. ‘Yes,’ he replied, ‘but it comes out of anger,’ a remark I have always thought as being as revealing about Hitchcock as about Marnie. Perhaps Pomerance thought the scene had been analysed extensively elsewhere and that he had nothing to add. One would have welcomed his intuitions nonetheless.

The other striking omission – to me, at least – is the complete absence of any reference to Bernard Herrmann’s score. Over the years this has become almost as controversial as the film itself, because it foreshadows the calamitous falling out between composer and director over the score for Hitchcock’s next film, Torn Curtain (1966). No one could dispute the importance of Herrmann’s contribution to Hitchcock’s films, from The Trouble with Harry (1955) to Marnie (1964), but a number of critics have suggested that Hitchcock felt that Herrmann was beginning to repeat himself. In Torn Music: Rejected Film Scores (2012), Gergely Hubai goes so far as to contend that ‘Hitchcock mostly blamed Herrmann for Marnie’s poor box-office showing, claiming that its old-fashioned style ruined his cutting edge “sex mystery”’.14 Memos at the time indicate that Hitchcock saw Marnie as a psychological suspense drama in the manner of Spellbound and that it should have a similar recurring musical theme, which Herrmann does indeed supply, though in his own distinctive style. It was actually quite unusual for Herrmann to highlight his main theme in that way. Although the theme itself is quite similar to one he composed for The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad (and indeed quite similar to Leonard Rosenman’s main theme for Rebel Without a Cause), he would have been entitled to quote Brahms when he was informed that a theme in the finale of his First Symphony was similar to a theme in the finale of Beethoven’s Ninth: ‘Any donkey can see that.’ The important point is how the theme is deployed and developed. In this regard, I would think back to Pomerance’s fine visual analysis of the early hotel room scene when our mysterious heroine rinses the black dye out of her hair in the bathroom before facing the camera for the first time as the archetypal Hitchcock blonde. ‘In the explosion of that proud, beautiful face inside the wet ring of sparkling hair,’ Pomerance enthuses, ‘we already love her.’15 What is missing from that exultant description is an acknowledgement of the essential way Herrmann’s music swells, contributes to, and indeed completes that moment. In the words of musicologist Christopher Palmer (1990), ‘the burst of musical technicolor’ at that point ‘makes it one of the most memorable images in the film.’16 One could multiply instances of that kind. For me, Herrmann’s score, which appropriately combines rich romanticism with disturbing dissonance, has always been an inseparable part of Marnie’s greatness.

Let me end on the film’s finale, and on the book’s eerie cover illustration, which grows more haunting the more you look at it. It is an image of the children playing in the street, as seen by Marnie when she emerges into daylight after exorcising the childhood trauma that has paralysed her emotional development. One can also just see at the end of the street that disconcerting ship, a clue all along that Marnie’s mental blockage might have some connection with it (a sailor being at the centre of her forgotten nightmare). The children are very oddly arranged in the frame and look slightly alien: is there a potential future Marnie amongst them? When Mark emerges from the house, Marnie tells him she does not want to go to prison but would rather stay with him. Is that the nearest she can come to a declaration of love, or is it simply an expression of her preference for one kind of imprisonment over another? Mark replies: ‘Had you, love?’ Pomerance astutely picks up on the curious expression and grammar of that response: ‘had you’ rather than ‘would you’; ‘a delicious subjunctive’, as he puts it, ‘which invokes a potent “if”.’17 If Marnie is right that what has excited and attracted Mark to her is the mystery of her background, how stands the relationship now the mystery has been solved? Wonderfully appropriate that this most enigmatic of films should end on an Ivesian Unanswered Question.

Joseph Conrad once said that he would rather have the faults of Dickens’s Bleak House than most other novels’ virtues; and one can feel the same about Marnie. It is a film one can love irrespective of its flaws; after all, that is what Mark does with Marnie. Pomerance’s splendid monograph is a love letter that reads like a thriller. Hitchcock would surely have been delighted…

November 2014

Robin Wood, Hitchcock’s Films (Tantivy Press, 1965). ↩

Tony Lee Moral, Hitchcock and the Making of Marnie (Manchester University Press, 2002). ↩

Donald Spoto, Spellbound by Beauty: Hitchcock and His Leading Ladies (Hutchinson, 2008). ↩

Alex von Tunzelman, ‘Do Hitchcock and The Girl reveal the horrible truth about Hitch?’, The Guardian, 11 January 2013, available here. ↩

Murray Pomerance, BFI Film Classics: Marnie (Palgrave Macmillan for British Film Institute, 2014), p. 48. ↩

Ibid, pp. 49-50. ↩

Ibid, p. 77. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Ibid, p. 34. ↩

Ibid, p. 35. ↩

William Rothman, Hitchcock: The Murderous Gaze, 2nd edition (University of New York Press, 2012). Quoted in Pomerance, p. 33. ↩

Pomerance, p. 37. ↩

Ibid, p. 9. ↩

Gergely Hubai, Torn Music: Rejected Film Scores (Silman James Press, 2012), p. 62. ↩

Pomerance, p. 8. ↩

Christopher Palmer, The Composer in Hollywood (Marion Boyars, 1990), p. 291. ↩

Pomerance, p. 83. ↩