by NEIL SINYARD

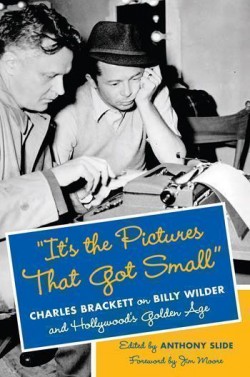

Book review: Anthony Slide (editor), “It’s the Pictures That Got Small”: Charles Brackett on Billy Wilder and Hollywood’s Golden Age (New York: Columbia University Press, December 2014), £23. 95.

After a brief spell at RKO, Charles Brackett became a staff writer then producer at Paramount from 1934 to 1949; and his journals covering that period provide a riveting perspective on the daily routine of a Hollywood studio in its prime. Brackett also became half of the most celebrated screenwriting partnership in Hollywood history. In just over ten years he and Billy Wilder collaborated on thirteen screenplays, most of them critical and commercial successes, some of them enduring classics of the screen. They wrote two of the greatest screen comedies of the late 1930s, Midnight for Mitchell Leisen and Ninotchka for Ernst Lubitsch (both 1939). After scripting Ball of Fire (1941) for Howard Hawks, they became a producer-director as well as writing team, with Brackett as producer and Wilder as director; and proceeded to make audacious trailblazing dramas such as The Lost Weekend (1945) and Sunset Boulevard (1950). As most film buffs will know, the title of this book is a famous line from Sunset Boulevard, when William Holden’s down-at-heel screenwriter has recognised a former star of the silent screen, Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) and said: ‘You used to be big.’ ‘I am big,’ she has retorted imperiously, ‘It’s the pictures that got small.’ Less well known is the fact that it was Charles Brackett who was savvy enough to see the importance of that moment and recommend that the line be re-shot in close-up, probably also sensing how it foretold the devastating final close-up of that magnificent film.

Sunset Boulevard was the culminating triumph of the Brackett-Wilder collaboration and it begs the question: why then did they split up? Shortly before his death in 1969, Brackett was asked that very question by the writer and biographer, Garson Kanin and, according to Kanin, he replied as follows: ‘I never understood it….it was such an unexpected blow, I thought I’d never recover from it….I loved working with him. It was so stimulating and pleasant.’1 Whether this is verbatim what Brackett said, or whether Kanin was creatively glossing the gist of what he thought he meant, or whether he was just giving his own spin on what he thought was the truth, has never been fully established. What is beyond dispute is that Kanin’s account of the break-up’s being sudden and unexpected could not have been wider of the mark. From Maurice Zolotov onwards, Wilder’s biographers have plotted in detail the persistent strains of the collaboration, but this is the first time that we have been told the tale entirely from Brackett’s point of view. From this account, the surprising thing is not that they split up but that they managed to stay together for so long.

On August 17, 1936, Brackett writes that ‘I am to be teamed with Billy Wilder, a young Austrian I’ve seen about for a year and like very much… He has the face of a naughty cherub.’2 Brackett can help Wilder with his then imperfect English, but it is not long before he is becoming irritated by what he sees as the young man’s pedantry, his arrogance, and his tendency to claim credit for ideas that have originated from his partner. As early as September 1938, he is welcoming the possibility of a permanent severance from Wilder, and this will develop into an almost annual refrain. On August 2, 1942, he is ‘wondering whether our successful collaboration is over.’3 On March 18, 1943, he writes: ‘Gravely doubt that I can ever bring myself to work with Billy again. At the moment the idea of doing so takes all the joy out of life.’4 Even after their Oscar-winning success with The Lost Weekend, the tensions in their fraught relationship show no signs of abatement. On August 18, 1947, Brackett records that ‘I am gloriously sure I will never write with him again’;5 and a little later he writes that ‘to work with Billy again is a prospect that makes my innards curl.’6 Contrary to Garson Kanin’s interpretation, by the time Brackett and Wilder got round to their greatest collaboration, Sunset Boulevard (which Brackett’s friend Christopher Isherwood was justifiably to call ‘the best thing ever done about Hollywood’), neither they nor anyone close to them seemed to have any doubts that this would prove the parting of the ways.

In any long-standing collaboration, one can expect occasional differences and even passionate disagreements, but this particular partnership seemed unusually volatile. On one occasion, Brackett, who was generally a mild-mannered man, became so incensed that he pulled the flute Wilder was playing from out of his mouth and broke it over his knee. A principal reason behind the constant conflict was that, in almost every way, they were complete opposites: temperamentally, emotionally and politically. Brackett was quietly spoken, modest and reserved; Wilder was loud, egotistical and extrovert. Brackett kept details of his personal life very much to himself; Wilder was constantly bringing his personal life into the office. Brackett was a diehard Republican; Wilder was a left-leaning Democrat. Unusually for a writing team such as this, the relationship was conducted entirely within office hours, for they were so different that their social lives very rarely intersected.

However, the fact that their partnership was entirely professional might go some way towards explaining why it endured for over a decade. Success helped, of course; but there is also no doubt that a bond they did share was a mutual professional respect. For all that Wilder drove him crazy, Brackett never doubted his exceptional talent nor the fineness of his dramatic mind. At one point he does acknowledge in his Journals that ‘he is not as good without Billy’, though, significantly, he adds that he thinks he is still ‘pretty good – and more self-respecting’.7 Some critics have felt that Wilder also was not as good without Brackett, who, as well as being creative in his own right, was a valuable touchstone and restraining influence, curbing his partner’s wilder excesses, as it were. This view was supported when Wilder’s first film after his break with Brackett, Ace in the Hole (1951) was a resounding flop. Wilder always insisted it was one of his greatest films (and I agree with him), but some felt that, away from Brackett’s civilised script counselling, he went too far in his tough critique of journalistic exploitation and gullible humanity and only succeeded in alienating both critics and audiences.

The book would be worth acquiring alone for its disturbing yet dazzling portrait of Billy Wilder, an authentic Hollywood genius if ever there was one. But this is only a part of what it has to offer. There are few more compelling accounts of the reality behind the romance of the Dream Factory, the daily grind of working in a big Hollywood studio, hammering away at your own scripts; occasionally being required to doctor other people’s; having to re-write after unsuccessful previews; or being at the behest of temperamental stars and tempestuous studio heads. At one stage he writes: ‘I am actually filthy of hair and scraggy of finger nail and unbarbered, to try and get something done for Paramount.’8 He never loses that sense of dedication and professional pride amidst all the entanglements of finance and ego with which he has to contend. Yet, for all his conservative leanings, he is no blind respecter of authority. He describes the head of Paramount, Adolph Zukor as ‘a tiny, dim little man sitting in his enormous office, like a mouse in a cake-box.’9 He is contemptuous of the way Goldwyn and DeMille bully and berate junior employees. And there are no stars in his eyes (and indeed a notable absence of heroes or role-models in the whole text) when it comes to dealing with Hollywood royalty. He is effortlessly unfazed when Joan Fontaine is having a critical spasm over a perfectly grammatical sentence which she claims is ungrammatical. On Ginger Rogers, he will write: ‘It is the old trouble with Ginger: she hasn’t a very good brain but she insists on using it.’10 He is tactfulness personified when pacifying Jean Arthur, who feels she is being deliberately upstaged by Marlene Dietrich in the Brackett-Wilder collaboration, A Foreign Affair (1948). In his Journal he reports the encounter thus: ‘“I have sex appeal,” she said calmly, but inaccurately…’11

What steadily emerges from the Journals is not simply a picture of Wilder and of Hollywood but also an unwitting self-portrait. Brackett was forty years old when he first came to Hollywood in 1932. A Harvard Law School graduate and a former drama critic of The New Yorker, he was a fringe member of the Algonquin Circle and had published a handful of short stories and novels, which these days are largely unread and almost totally forgotten. Even his most famous novel, Entirely Surrounded (1934), satirising the Algonquin set and personalities such as Dorothy Parker and Alexander Woollcott, was to be upstaged by the Moss Hart and George Kaufman Broadway hit, The Man Who Came to Dinner (1939), with its thinly disguised portrait of Woollcott possibly influenced by Brackett’s portrayal. He might have come to Hollywood in a disdainful frame of mind (in his excellent introduction, Anthony Slide does suggest that Brackett was something of a snob), but he also recognised that what he had achieved thus far in his career was unspectacular. ‘I have an interesting, scattered life,’ he wrote in 1942, ‘and have gotten nowhere, and I am getting nowhere.’12 Whatever else could be said about his time in Hollywood, he certainly got somewhere.

In his deeply sympathetic and loving Foreword to the book, his grandson, Jim Moore describes Brackett as ‘a lonely man, prone to deep introspection and self-loathing.’13 Certainly the impression given in the book is that of a serious, rather mysterious person who in Hollywood commanded respect more than affection. He does not give much of himself away. We learn next to nothing about his social life away from the movies or the kind of music he likes, say, or the kind of reading he enjoys in his spare time. He is discreet about his sexual life to the point where a number of commentators on the Hollywood scene have concluded, without any evidence other than conjecture, that he was a repressed homosexual. (Anthony Slide deals with this matter thoroughly in the Introduction; Jim Moore more or less says, ‘So what?’). His family life certainly seems to have been an unhappy one, involving the alcoholic depression of his first wife and the violent death of his elder daughter; but we must await Jim Moore’s promised biography to learn more of this.

If all this might suggest that the Journals are unexciting and unrevealing, this is certainly not the case, for although he might seem evasive on some personal issues, he is remarkably outspoken in his opinions and preferences where people are concerned. Indeed, in contrast to the way he seemed to present a façade of gentlemanly calm to his employers and peers, the Journals positively bristle with invective, as if they are letting something out of his system. Dr Johnson always professed to like a ‘good hater’ and Brackett was a very good hater; mere dislike never seemed sufficient. So he describes Charles Laughton as ‘the most repellent human being with whom I have ever had to share a table’,14 a dubious accolade he will transfer to Charlie Chaplin a decade later. ‘A day at Howard Hawks’s is always a day of hell’, he writes, as they confer on the screenplay for Ball of Fire.15 Anatole Litvak is described as ‘detestable’;16 and he dislikes Frank Capra ‘intensely’.17 He is equally rude about a whole range of actors and actresses. Some of these outbursts perhaps derive from a sense of personal frustration but many of them seem prompted by his antipathy to anyone belonging to the political Left. ‘He had no problem in dealing with, and maintaining a friendship with those fellow writers with a strong liberal slant,’ writes Anthony Slide in his Introduction.18 This is certainly not the impression one gets from the text, where Brackett loses no opportunity to disparage the views and even the dress sense of the likes of, for example, Clifford Odets, John Dos Passos, John Garfield, Elia Kazan, Orson Welles and Philip Dunne.19 Yet one always suspects that we are being made privy to private thoughts here rather than public utterances. He might have been steadfast in his views, but there is no record of his being dogmatic or discourteous: quite the contrary. Indeed, as a counterbalance, one should also note his horror at hearing over the radio Adolph Menjou’s despicable denunciation of all Democrats as Communists during the HUAC investigations of Hollywood.20 Solid Republican that he is, even Brackett balks at the extreme right-wing utterances of the appalling Hedda Hopper, feeling the need, after two meetings with her in one week, to be, as he put it, ‘disinfected… and to divide my goods and give them to the poor.’21 In January 1938, he wrote: ‘Wish I didn’t suspect in myself a nasty rightishness, and hope devoutly I never let it make me unfaithful to Democracy, who is really my lady.’22 This commitment will have been tested during the post-war political turmoil in Hollywood, but he appears never to have deviated from this fidelity. He was a man of conviction, but also a model of fairness and integrity, with an engaging streak of self-criticism and self-deprecation.

Will there be a second volume? One hopes so, for what happened to Brackett and Wilder after their split is equally fascinating. Wilder went on to even greater successes and discovered a writing partner, I.A.L. Diamond who was to prove completely compatible (or maybe Wilder had mellowed by then). It culminated with Wilder achieving a personal triple-Oscar triumph with The Apartment (1960), after which, like most directors of his generation, he found the going increasingly tough in a changing Hollywood. Although they were less prestigious, Brackett also had his fair share of successes post-Wilder: an Oscar for his contribution to the screenplay for the 1953 version of Titanic; the producer of solid and varied mainstream hits such as the thriller, Niagara (1953), the musical, The King and I (1956) and the fantasy adventure, Journey to the Center of the Earth (1959). His final years were dogged by ill-health; and his brutal (and unlawful) sacking by Twentieth Century Fox following the reinstatement of Darryl Zanuck could only have fuelled his disillusionment with the industry.

In a Journal entry of August 29, 1942, he records that he has been to see Holiday Inn, best remembered now as the film which first featured Irving Berlin’s ‘White Christmas’. ‘It is the type of picture,’ he writes, ‘which, while not unpleasant in the least, makes one ashamed of being connected with the pictures.’23 Why? Throughout the Journals there is a sense that Brackett never really adjusted to the film world or respected or valued his contribution to it, and might even have had delusions of a more respectable and successful literary career that corresponded more closely to his idea of personal fulfilment. Yet he had no reason to be feel any disappointment with his achievement. His work with Wilder will endure for as long as cinema itself; and even without Wilder, his name on the credits invariably guaranteed a film of taste and integrity. This superbly edited and annotated book is a worthy testimony to a troubled individual in an industry he unjustly denigrated but which he undoubtedly enriched.

See Garson Kanin, Hollywood, p. 164. ↩

Anthony Slide (editor), “It’s the Pictures That Got Small”: Charles Brackett on Billy Wilder and Hollywood’s Golden Age (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014), p. 87. ↩

Ibid, p. 189. ↩

Ibid, p. 213. ↩

Ibid, p. 302. ↩

Ibid, p. 328. ↩

Ibid, p. 216. ↩

Ibid, p. 7. ↩

Ibid, p. 122. ↩

Ibid, p. 246. ↩

Ibid, p. 314. In fairness to Jean Arthur, she may have had a point. Andrew Sarris never quite forgave Wilder for what he called his ‘needless brutalisation of Jean Arthur in A Foreign Affair‘ – see Andrew Sarris, You Ain’t Heard Nothing Yet: The American Talking Film: History and Memory, 1927-1949, p. 327. Richard Corliss wrote that ‘she is made to wear what, after much morbid consideration, I can only describe as the ugliest dress in a forties movie’ – Richard Corliss, Talking Pictures: Screenwriters in the American Cinema, p. 146. I would nominate Jeanne Craine’s dress in Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s A Letter to Three Wives (1949) as a close runner-up. ↩

Slide (editor), “It’s the Pictures That Got Small”, p. vxv. ↩

Ibid, p. xvii. ↩

Ibid, p. 60. ↩

Ibid, p. 61. ↩

Ibid, p. 356. ↩

Ibid, p. 233. ↩

Ibid, p. 5. ↩

The writer (and later director) Philip Dunne was one of the most prominent liberals in the American film industry at this time, particularly admired for his screenplays for John Ford’s Oscar-winning How Green was my Valley (1941) and Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s romantic masterpiece, The Ghost and Mrs Muir (1947). Whenever he appears within Brackett’s sights, he is disparaged as being at best ‘dull’ and at worst ‘the most unendurable young man I know, an absolutely stinker’ – Ibid, p. 379. Ironically, in Dunne’s own memoir, Take Two: Life in Movies and Politics, a superb account of politics and power in Hollywood, his references to Brackett are unfailingly respectful, even though he recognises they are at opposite ends of the political spectrum. They were to work together in the 1950s, even though in his Journals, Brackett thought the prospect unimaginable. ↩

Slide (editor), “It’s the Pictures That Got Small”, p. 295. ↩

Ibid, p. 219. ↩

Ibid, p. 110. ↩

Ibid, p. 191. ↩