by NEIL SINYARD

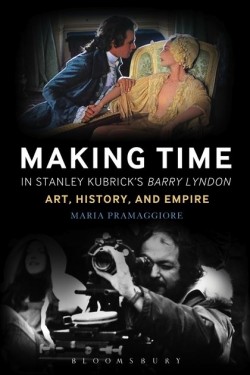

Book review: Maria Pramaggiore, Making Time in Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon: Art, History, and Empire (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2015), £16.99, 216pp.

Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975) was a modern adaptation of William Makepeace Thackeray’s Victorian novel about the rise and fall of an 18th century scoundrel. To put it another way, it was an adaptation by an American film-maker of an English novel set in Ireland. The significance of these temporal and national disjunctions are at the heart of the argument behind this stimulating new book on what has long seemed to me Kubrick’s greatest movie. In America, it was the most commercially unsuccessful film of his career and was memorably lampooned by MAD magazine under the title of Borey Lyndon. In the final chapter, assessing the place of the film in the context of 1970s cinema, Maria Pramaggiore suggests that its failure with American audiences was to do with its ‘non-Americanness and its non-manliness’.1 This book sets itself the task of examining the highly original way ‘emotion and thought find a place in the rhythms of the film’.2

Kubrick’s modernist sensibility was often expressed through the complicated time-structures of his films, which rarely followed conventional chronology. This was as pronounced in early films like Killer’s Kiss (1955), The Killing (1956), and Lolita (1961) as it was in later works such as 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and The Shining (1980). ‘In Kubrick’s universe,’ Pramaggiore writes, ‘the past and the future are never far apart.’3 She is alert to the fact that the way time passes is very important in a Kubrick film, and also very important for the way an audience responds. Certainly many critics at the time found Barry Lyndon cold and slow-moving (which has always been the exact opposite of my experience), and thought that whatever drama the tale contained tended to collapse into a series of pretty pictures. Whilst Pramaggiore is very good at illustrating and discussing the portraits and paintings that might have inspired Kubrick’s compositions, she appreciates more importantly what is behind these civilised surfaces, and how Kubrick, like Thackeray in his novel, is delivering a lethal critique of social hierarchy and hypocrisy. In a succinct sentence she summarises the entire thrust of the film when she characterises Kubrick’s understanding of his hero as ‘a hot-headed Irishman with a proclivity towards violence, who has become trapped within an artfully arranged picturesque landscape, a land to which he has no claims and a place where he does not belong.’4 She is right, I think, to suggest that, by the end, Kubrick is more sympathetic to the hero than Thackeray was, a sympathy perhaps deriving from his American perspective that traditionally values iconoclasm and independence and also from his perception of the difficulties of an outsider Irishman trying to progress through the forbidding corridors of British military and aristocratic power. In the novel, the hero is a rogue and a hypocrite who gets his deserved comeuppance. In the film, he is a more complex figure, at times brutal and unscrupulous, at other times pathetic and vulnerable, and finally undone when playing by the rules of a society whose acceptance he covets but which fundamentally despises him.

There is an interesting account of the production background of the film; and we are usefully reminded that its genesis might have arisen out of Kubrick’s now legendary aborted Napoleon project. (The narrative of Barry Lyndon ends quite pointedly in 1789.) Among a host of thought-provoking insights, the author makes a suggestive comparison between Kubrick and Max Ophuls (a director Kubrick much admired), but this time in terms of music and characterisation more than visual style, which is how the comparison is usually conducted. If Barry Lyndon is sometimes seen as being something of an anomaly in this director’s work, Pramaggiore shows convincingly that it abounds with familiar traits, such as his fascination with the military, which links the film with Paths of Glory (1957), Spartacus (1960), Dr Strangelove (1964) and Full Metal Jacket (1987), and with authority figures ‘who find an obscene enjoyment in their roles.’5 She is attentive to the ominous symmetry of the film’s construction, noting, for example, how the loss of Barry’s father in literally the first shot of the film foretells the sorry fate of father figures throughout, with Barry himself ending up as the sorriest father figure of them all. (I had not noticed before the significant role that horses play in Barry’s gathering misfortune, culminating in a duel in a stable that will literally cripple his future.) In contrast to what seems, for the most part, a statically composed film, she notes that there are two outbursts of violence filmed with a handheld camera that emphasise the shift in Barry’s fortunes. The first shows his victorious fist-fight against a fellow soldier, which momentarily seems to lift his prospects; the second shows his disastrous uncontrolled attack on his stepson during a music recital, a savage violation of decorum which will bring his upward social mobility to an abrupt end. Deadly duels open and close the film, both predicated on gentlemanly codes of honour but whose outcomes will prove traumatic.

In her opening page, Pramaggiore picks up a telling parallel between Kubrick’s film and The Sopranos, and the violence in both which lurks beneath the civilised conduct. Forty years on, Barry Lyndon, she proposes, ‘still has something important to say about image-making, culture and power.’6 Over the book’s succeeding pages, she proceeds to demonstrate that importance with eloquence and authority. When I was contacted by Sight and Sound in 2012 for my choice of films in its ten-yearly round-up to find the All-Time Greatest Movies, I put Barry Lyndon in my Top Ten. After reading this book, I have not had second thoughts.

Pingback: Barry Lyndon | Neil Sinyard on Film