by NEIL SINYARD

The following is a slightly edited transcript of the audio commentary I gave for the Criterion Classics DVD release of Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole. (I was also interviewed about the film on the Masters of Cinema DVD/blu ray release.) This essay will probably make more sense if you have viewed the film recently. I’ve kept the relatively informal style and hope the commentary will be of interest. For a number of reasons, personal and artistic, no director has been more important to me than Billy Wilder.

Plain credits on a parched, soil surface: Ace in the Hole announces itself immediately as a gritty film featuring characters with hearts of stone. The name that dominates the credits is writer/producer/director Billy Wilder; and Ace in the Hole (1951) is following on from such hard-hitting Wilder movies as Double Indemnity in 1944, The Lost Weekend in 1945 and Sunset Boulevard in 1950 which shone a harsh spotlight on unsavoury aspects of American life. Like other acclaimed writer-directors of the 1940s in Hollywood, such as Preston Sturges, John Huston and Joseph L.Mankiewicz, Wilder had become a director to protect his own scripts. ‘It isn’t important that a director knows how to write,’ he would say, ‘but it is important that he knows how to read.’

Plain credits on a parched, soil surface: Ace in the Hole announces itself immediately as a gritty film featuring characters with hearts of stone. The name that dominates the credits is writer/producer/director Billy Wilder; and Ace in the Hole (1951) is following on from such hard-hitting Wilder movies as Double Indemnity in 1944, The Lost Weekend in 1945 and Sunset Boulevard in 1950 which shone a harsh spotlight on unsavoury aspects of American life. Like other acclaimed writer-directors of the 1940s in Hollywood, such as Preston Sturges, John Huston and Joseph L.Mankiewicz, Wilder had become a director to protect his own scripts. ‘It isn’t important that a director knows how to write,’ he would say, ‘but it is important that he knows how to read.’

‘Tell the Truth’: Enter Chuck Tatum

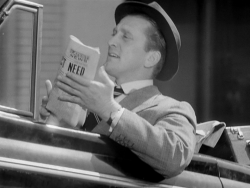

Wilder was very adroit at giving his main characters memorable entrances – think of Marilyn Monroe’s first entry as Sugar Kane in Some like it Hot (1959) where she gets a wolf whistle from a train – and Kirk Douglas’s first appearance as Chuck Tatum, as he is towed into Albuquerque, is appropriately unorthodox here. Wilder is establishing three things very quickly: that Tatum is down on his luck; that he is nevertheless good at exploiting even adverse situations to his advantage, so he gives the appearance of being chauffeured into town; and also that he is interested in newspapers – and looking around for the next angle or opportunity.

Passing the offices of the Albuquerque Sun Bulletin he will see his chance. As he enters the office, he passes a Native American cutting up pictures for the front page, ‘How,’ he says. ‘Good afternoon, sir,’ replies the man. That’s a slight exchange but a significant one. It shows quickly Tatum’s cockiness, sarcasm, even racial insensitivity, all qualities that are to have some importance in the revelation of his character.

Passing the offices of the Albuquerque Sun Bulletin he will see his chance. As he enters the office, he passes a Native American cutting up pictures for the front page, ‘How,’ he says. ‘Good afternoon, sir,’ replies the man. That’s a slight exchange but a significant one. It shows quickly Tatum’s cockiness, sarcasm, even racial insensitivity, all qualities that are to have some importance in the revelation of his character.

Cherish the moment when he enters the office and surveys a scene of busy routine, almost more like a schoolroom than a newsroom: it is one of the few occasions, certainly in the early part of the film, where he is quiet. But he is doing what he often does in such moments: sizing things up. He moves to the front of the frame as if in assertion of his own ego: no question in his mind that he should occupy centre stage.

Cherish the moment when he enters the office and surveys a scene of busy routine, almost more like a schoolroom than a newsroom: it is one of the few occasions, certainly in the early part of the film, where he is quiet. But he is doing what he often does in such moments: sizing things up. He moves to the front of the frame as if in assertion of his own ego: no question in his mind that he should occupy centre stage.

Whereas most people might say ‘Excuse me’, Tatum rings for attention: a slide of the typewriter carriage whose ‘ping’ announces his presence and demands service. It’s an incisive metaphor for the way he uses a typewriter to grab attention (the essence of his profession, in his eyes). When Herbie goes to tell his boss that Charles Tatum from New York is here to see him with a scheme that will make him $200, Tatum uses the typewriter carriage to ignite his match for his cigarette – nothing as ordinary as a matchbox for Chuck: he has, as one might say, flair. The brief exchange with the cub reporter, Herbie, played by Bob Arthur, has a nice moment too, presaging their future friendship. When Herbie returns Chuck’s ‘cagey, eh?’ there’s a flicker of acknowledgement in Chuck’s face as if sensing he has found someone with a little spark.

Whereas most people might say ‘Excuse me’, Tatum rings for attention: a slide of the typewriter carriage whose ‘ping’ announces his presence and demands service. It’s an incisive metaphor for the way he uses a typewriter to grab attention (the essence of his profession, in his eyes). When Herbie goes to tell his boss that Charles Tatum from New York is here to see him with a scheme that will make him $200, Tatum uses the typewriter carriage to ignite his match for his cigarette – nothing as ordinary as a matchbox for Chuck: he has, as one might say, flair. The brief exchange with the cub reporter, Herbie, played by Bob Arthur, has a nice moment too, presaging their future friendship. When Herbie returns Chuck’s ‘cagey, eh?’ there’s a flicker of acknowledgement in Chuck’s face as if sensing he has found someone with a little spark.

There is another key detail in this scene: Mr Boot’s sign ‘Tell the Truth’ which Tatum surveys with some amusement. There’s a double-edged irony here: in one sense, the sign is a perfect representation of him, because precisely what he does is embroider the truth; but much later in the film, when he does try to tell the truth, nobody wants to listen.

There is another key detail in this scene: Mr Boot’s sign ‘Tell the Truth’ which Tatum surveys with some amusement. There’s a double-edged irony here: in one sense, the sign is a perfect representation of him, because precisely what he does is embroider the truth; but much later in the film, when he does try to tell the truth, nobody wants to listen.

Mr Boot is played by one of Hollywood’s most reliable supporting players of the time, Porter Hall, who was in Double Indemnity as the passenger on the observation car on that fateful train, and whom I particularly remember as one of the studio bosses trying to dissuade Joel McRae’s idealistic director from making ‘O Brother where art thou?’ in Preston Sturges’s dark satire about Hollywood, Sullivan Travels (1941). The scene resembles an early scene in Sunset Boulevard when William Holden’s down-at-heel screenwriter has to make a sales pitch to a potential employer who seems hard to impress. However, whereas Holden’s screenwriter tries at least to charm his way into the boss’s good graces, Tatum wears his arrogance like a red badge of courage. ‘Even for Albuquerque this is very Albuquerque,’ he sniffs, contemptuously, when offering his opinion on Boot’s newspaper. Tatum’s pitch emphasises his big-city expertise. He knows newspapers backwards and sideways and can write to order: if there’s no news, he says, he’ll go out and bite a dog. So what is he doing in Albuquerque, a $250 a week newspaperman offering his services for $50?

Wilder once again makes shrewd use of Boot’s ‘Tell the Truth’ notice to make a point. Tatum advertises his credentials but shows how observant he is: he could lie pretty well, he says, but he would never lie to man who wears belt and suspenders, because that betokens a cautious man who would check his facts. (A similar character, incidentally, crops up in Wilder’s The Spirit of St Louis.) Boot is unfazed by this revelation of journalistic brilliance compromised by human frailty, but the character seems extreme even for Wilder (a director famously described by William Holden as ‘a man with a mind full of razor blades’) and at this juncture it might be worth saying something about the casting and screen persona of Kirk Douglas.

Wilder once again makes shrewd use of Boot’s ‘Tell the Truth’ notice to make a point. Tatum advertises his credentials but shows how observant he is: he could lie pretty well, he says, but he would never lie to man who wears belt and suspenders, because that betokens a cautious man who would check his facts. (A similar character, incidentally, crops up in Wilder’s The Spirit of St Louis.) Boot is unfazed by this revelation of journalistic brilliance compromised by human frailty, but the character seems extreme even for Wilder (a director famously described by William Holden as ‘a man with a mind full of razor blades’) and at this juncture it might be worth saying something about the casting and screen persona of Kirk Douglas.

Born Issur Danielovitch Demsky and son of an immigrant Russian-Jewish ragman, Douglas had begun his film career after World War Two and had played a range of roles, from the villain in the classic film noir Build My Gallows High in 1947 to a teacher in Joseph Mankiewicz’s Oscar-winning A Letter to Three Wives in 1949 to an exceptionally charming gentleman caller in the film version of Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie in 1950. But the part that particularly defined his screen personality at this time, which was his first starring role and his first Oscar nomination, was the boxer in Champion (1949), a man who will stop at nothing in his ruthless drive to get to the top. Douglas was one of a new breed of stars who could make an anti-hero fascinating; and, with a director who was also not afraid to go against the grain, it makes for an abrasive combination. Even Douglas asked if the character might be given a bit more charm, but Wilder refused. ‘Give it both knees, right from the beginning,’ he told him.

Yet I think Wilder still manages very cannily to suggest a vulnerability in Tatum that just occasionally pierces his armour of arrogance. I’m intrigued by the small detail that during the scene he keeps lowering his price, from 50 to 45, to 40 per week: for all the bravado, he really badly wants this job. He gives the reason why in a striking low angle shot that makes him look menacing but at the same time gives the impression of his momentarily staring into an abyss: that he’s burnt his boats as well as the bearings on his convertible and his only chance back now is a break in a small newspaper that will have the wire services clamouring for his skills. ‘When they need you, they forgive and forget,’ he says. It’s hard not to feel that Wilder might have had Hollywood in his mind when composing that line. When watching Tatum at this point – where there seems to be both fire and fear in what he says – I think of that Scott Fitzgerald maxim in his uncompleted final novel about Hollywood, The Last Tycoon: ‘There are no second acts in American lives’.

Yet I think Wilder still manages very cannily to suggest a vulnerability in Tatum that just occasionally pierces his armour of arrogance. I’m intrigued by the small detail that during the scene he keeps lowering his price, from 50 to 45, to 40 per week: for all the bravado, he really badly wants this job. He gives the reason why in a striking low angle shot that makes him look menacing but at the same time gives the impression of his momentarily staring into an abyss: that he’s burnt his boats as well as the bearings on his convertible and his only chance back now is a break in a small newspaper that will have the wire services clamouring for his skills. ‘When they need you, they forgive and forget,’ he says. It’s hard not to feel that Wilder might have had Hollywood in his mind when composing that line. When watching Tatum at this point – where there seems to be both fire and fear in what he says – I think of that Scott Fitzgerald maxim in his uncompleted final novel about Hollywood, The Last Tycoon: ‘There are no second acts in American lives’.

Land of entrapment

There’s a great shot when he comes out of Boot’s office and they point to his desk. The camera placement actually anticipates the very last shot of the film, when Tatum will be back where he started – only worse. He walks directly to the front of the frame at which point the screen goes black, in a device that seems to me Wilder has stolen directly from Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope, his famous ten-minute-take film of 1948, played out in continuous time and where the transition from one reel to the next was contrived through a character walking directly in front of the camera to enable the transition to be made. Whereas Rope used it to maintain an illusion of continuous time, Wilder deploys it to mark a time lapse. When Tatum strides back away from the camera, a year has passed: the camera’s immobility matches that of Tatum’s progress. There’s a nifty touch of costuming too: notice that now he is wearing both belt and suspenders, perhaps in mock homage to Boot’s hold over him; but he is also wearing a black shirt which sets him apart from the other people in the room but also has uncomfortable connotations from Europe’s recent past. He will be wearing it constantly as he begins to exert a dictator-like grasp of the media’s potential to help him develop his scheme; when this grip starts to slip, it will be signalled by a change of clothing.

There’s a great shot when he comes out of Boot’s office and they point to his desk. The camera placement actually anticipates the very last shot of the film, when Tatum will be back where he started – only worse. He walks directly to the front of the frame at which point the screen goes black, in a device that seems to me Wilder has stolen directly from Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope, his famous ten-minute-take film of 1948, played out in continuous time and where the transition from one reel to the next was contrived through a character walking directly in front of the camera to enable the transition to be made. Whereas Rope used it to maintain an illusion of continuous time, Wilder deploys it to mark a time lapse. When Tatum strides back away from the camera, a year has passed: the camera’s immobility matches that of Tatum’s progress. There’s a nifty touch of costuming too: notice that now he is wearing both belt and suspenders, perhaps in mock homage to Boot’s hold over him; but he is also wearing a black shirt which sets him apart from the other people in the room but also has uncomfortable connotations from Europe’s recent past. He will be wearing it constantly as he begins to exert a dictator-like grasp of the media’s potential to help him develop his scheme; when this grip starts to slip, it will be signalled by a change of clothing.

‘Thanks, Geronimo,’ he says to his co-worker when his lunch is delivered. The casually racist remark rankles – as it is meant to do, for later he is to become involved in matters that the Native Americans hold sacred. To Tatum – and to invoke the title of another great newspaper movie – nothing’s sacred. Even the words of President Roosevelt are parodied when he cites that day as one that will live in infamy – they have stopped serving him chopped chicken livers. As he starts complaining about the food, it’s clear that something is eating him. Behind his desk is a sign that reads ‘New Mexico – Land of Enchantment’ – but for Tatum it is a land of entrapment, a ‘sun-baked Siberia’, as he puts it, and it sets him off on what is clearly a familiar tirade against the quality of life there and what he was used to. ‘No Yogi Barra,’ he shouts and then asks Miss Deverish if she knows who Yogi Barra is. (Actually Kirk Douglas himself didn’t pick up that reference and had to have it explained to him by his secretary – that Yogi Barra was a legendary catcher for the New York Yankees. Wilder always delighted in slipping in references to American sports.) ‘Yogi…’ she replies, ‘it’s a sort of religion, isn’t it?’ Tatum picks up the analogy and runs with it, but in her quiet way, Miss Deverish is alluding again to a potential religious sub-theme that will be developed later.

‘Thanks, Geronimo,’ he says to his co-worker when his lunch is delivered. The casually racist remark rankles – as it is meant to do, for later he is to become involved in matters that the Native Americans hold sacred. To Tatum – and to invoke the title of another great newspaper movie – nothing’s sacred. Even the words of President Roosevelt are parodied when he cites that day as one that will live in infamy – they have stopped serving him chopped chicken livers. As he starts complaining about the food, it’s clear that something is eating him. Behind his desk is a sign that reads ‘New Mexico – Land of Enchantment’ – but for Tatum it is a land of entrapment, a ‘sun-baked Siberia’, as he puts it, and it sets him off on what is clearly a familiar tirade against the quality of life there and what he was used to. ‘No Yogi Barra,’ he shouts and then asks Miss Deverish if she knows who Yogi Barra is. (Actually Kirk Douglas himself didn’t pick up that reference and had to have it explained to him by his secretary – that Yogi Barra was a legendary catcher for the New York Yankees. Wilder always delighted in slipping in references to American sports.) ‘Yogi…’ she replies, ‘it’s a sort of religion, isn’t it?’ Tatum picks up the analogy and runs with it, but in her quiet way, Miss Deverish is alluding again to a potential religious sub-theme that will be developed later.

‘What do you do for NOISE around here?’ he shouts – so loudly that we can see newsmen in an adjoining room looking through the window to see what the commotion is about. It’s obviously a much repeated wail, as Herbie points out – ‘Is this is one of your long-playing records, Chuck?’ – but notice how unobtrusively Wilder suggests that at least Tatum and Herbie have grown a little closer over the year: Herbie now calls him ‘Chuck’ and now ignites his match for him by repeating the routine with the typewriter carriage, like the famous routine with cigar and match shared between Fred MacMurray and Edward G.Robinson in Double Indemnity to suggest their friendship. Tatum is still looking for that elusive break, which he evocatively describes as the ‘loaf of bread with a file in it’. He paces the newsroom like a prisoner in a cell, and the imagery of prison, of feeling trapped – literally and metaphorically – is to be a pervasive motif.

Nevertheless, although one might deplore the sentiments, one is drawn to the dynamism: it’s a dichotomy that will provide a major source of the film’s dramatic tension. He is, after all, the only source of movement and vitality in the office: he’ll be the film’s driving force. And as in the earlier scene prior to his meeting with Boot, he will start pulling the leg of Miss Deverish, suggesting she involves herself in a trunk murder (another sly allusion to Rope, perhaps?) and growls, as if wishing to put a tiger in her tank. Miss Deverish, incidentally, is played by one of those infallible Hollywood supporting players, Edith Evanson. She is forever associated in my mind with that figure of Fate she plays in Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat (1953), limping bravely towards the camera to disclose at great personal risk a crucial piece of evidence to Glenn Ford’s vengeful cop that will set him on the path to justice.

We have seen Boot enter unnoticed by Tatum – not the only time in the film he is to do that, appearing like a headmaster behind a naughty pupil who is acting up in class. He even thinks he has caught out Tatum drinking on the job: earlier he has told him of the drinking ban at work and asked if Tatum drank a lot. ‘Not a lot but frequently,’ is Tatum’s reply. Along with his clothing, alcohol will be another later signifier of his loss of control: he can resist temptation when things are going well, but when things deteriorate, so does he. In this instance, like many a Wilder protagonist, Boot has misread a visual image because he has not seen the complete picture. The bottle is in fact for Tatum’s model ship made out of matches and toothpicks: ingenious, but an object that signifies Tatum’s feelings of boredom and also perhaps of claustrophobia. Coverage of a rattlesnake hunt will at least get him out of the office – and maybe out of a rut.

‘Good news is no news’

What I like about the little scene that follows between Tatum and Herbie as they drive to the hunt is its purpose of progression. Ostensibly, it’s just a nice contrast to the Albuquerque scenes which, in their interiority, were getting a little claustrophobic. We see Tatum relaxing, as before being chauffeured to his next assignment. It’s developing a bit further the budding friendship between Tatum and Herbie, with Herbie as a useful foil to Tatum: he gives him someone to talk to; his callow attitudes are contrasted with Tatum’s outrageousness, giving us something to measure it against; but Herbie almost at times becomes representative of the audience, taken aback by the way Tatum’s mind works. Whereas Herbie thinks the rattlesnake hunt might be more exciting than Tatum gives it credit for, Tatum suggests that the thing that would make it really exciting would be if 50 rattlesnakes escaped and they were rounded up until one was unaccounted for. ‘Where’s the last rattler?’ Herbie asks. ‘In my desk drawer, fan.’ Wilder is already preparing the way for Tatum’s handling of the cave-in story (and, in a way, also preparing the way for the appearance of the Sheriff, who keeps a pet rattlesnake in a box). When Tatum stumbles across it, it’s as if the groundwork has already been cleared in his mind. And we’re seeing the contrast between Tatum’s style of journalism and that of Herbie, brought up under the ‘Tell the Truth’ tutelage of Mr Boot. What has Herbie learned from Tatum? ‘Bad news sells best because good news is no news.’

What I like about the little scene that follows between Tatum and Herbie as they drive to the hunt is its purpose of progression. Ostensibly, it’s just a nice contrast to the Albuquerque scenes which, in their interiority, were getting a little claustrophobic. We see Tatum relaxing, as before being chauffeured to his next assignment. It’s developing a bit further the budding friendship between Tatum and Herbie, with Herbie as a useful foil to Tatum: he gives him someone to talk to; his callow attitudes are contrasted with Tatum’s outrageousness, giving us something to measure it against; but Herbie almost at times becomes representative of the audience, taken aback by the way Tatum’s mind works. Whereas Herbie thinks the rattlesnake hunt might be more exciting than Tatum gives it credit for, Tatum suggests that the thing that would make it really exciting would be if 50 rattlesnakes escaped and they were rounded up until one was unaccounted for. ‘Where’s the last rattler?’ Herbie asks. ‘In my desk drawer, fan.’ Wilder is already preparing the way for Tatum’s handling of the cave-in story (and, in a way, also preparing the way for the appearance of the Sheriff, who keeps a pet rattlesnake in a box). When Tatum stumbles across it, it’s as if the groundwork has already been cleared in his mind. And we’re seeing the contrast between Tatum’s style of journalism and that of Herbie, brought up under the ‘Tell the Truth’ tutelage of Mr Boot. What has Herbie learned from Tatum? ‘Bad news sells best because good news is no news.’

There’s a nice sense of pacing and contrast in the next passage as well as delayed dramatic revelation that adds to the suspense. Wilder is close now to the core situation of his drama and he wants to lead you into it gradually and drop a few clues to add intrigue before the full revelation. The shot from inside the store window is an indicator of that. It is the most striking shot of the film so far and signalling something very significant is occurring inside or about to be revealed there.

There’s a nice sense of pacing and contrast in the next passage as well as delayed dramatic revelation that adds to the suspense. Wilder is close now to the core situation of his drama and he wants to lead you into it gradually and drop a few clues to add intrigue before the full revelation. The shot from inside the store window is an indicator of that. It is the most striking shot of the film so far and signalling something very significant is occurring inside or about to be revealed there.

Narrative curiosity is sustained a little longer as Herbie comes across an old lady fervently praying. Herbie’s intrusion feels like something of a sacrilege (an anticipation on a minor scale of a future dramatic theme) but our curiosity is furthered by the fact that the woman takes no notice of him and indeed seems unaware of his entry. Clearly the subject of her prayer is the entire focus of her attention which in turns hints at its seriousness. It’s a nice touch that Herbie doesn’t immediately grasp the significance of all this, certainly in terms of its potential for a story: he’s just puzzled and intrigued. But when he comes out to tell Tatum about it, Tatum’s antennae are immediately on the alert (‘Praying?’) and almost simultaneously a police siren is heard, connecting these two things. There’s a dark irony here: a feeling that he instinctively and almost immediately senses that this might be what he’s been looking for – or, in other words, that this might be the answer to his prayer. There’s time for him to make another crack in racially-dubious taste – ‘Maybe they’ve got a warrant for Sitting Bull for that Custer rap’ – before they drive to investigate what is happening, passing the sign that advertises the mine that was discovered by the Indians 450 years ago. Entry is free: it won’t stay that way for long.

Narrative curiosity is sustained a little longer as Herbie comes across an old lady fervently praying. Herbie’s intrusion feels like something of a sacrilege (an anticipation on a minor scale of a future dramatic theme) but our curiosity is furthered by the fact that the woman takes no notice of him and indeed seems unaware of his entry. Clearly the subject of her prayer is the entire focus of her attention which in turns hints at its seriousness. It’s a nice touch that Herbie doesn’t immediately grasp the significance of all this, certainly in terms of its potential for a story: he’s just puzzled and intrigued. But when he comes out to tell Tatum about it, Tatum’s antennae are immediately on the alert (‘Praying?’) and almost simultaneously a police siren is heard, connecting these two things. There’s a dark irony here: a feeling that he instinctively and almost immediately senses that this might be what he’s been looking for – or, in other words, that this might be the answer to his prayer. There’s time for him to make another crack in racially-dubious taste – ‘Maybe they’ve got a warrant for Sitting Bull for that Custer rap’ – before they drive to investigate what is happening, passing the sign that advertises the mine that was discovered by the Indians 450 years ago. Entry is free: it won’t stay that way for long.

Enter the Minosas

We are introduced to the film’s other key character, Lorraine Minosa (Jan Sterling) – a sweet-sounding name for one of the sourest characters in the whole of Wilder’s work. Skilful dramatist that he is, Wilder not only uses the character’s appearance for dramatic exposition but to push the narrative a little further, just through one phrase she uses about her husband: ‘dumb cluck’. It’s an immediate revelation of her attitude: that he had it coming, and that she’s more angry than anxious. At this point Tatum goes a bit quiet, letting Lorraine disclose herself in her own words, obviously sizing her up, and picking up not only her exasperation at her husband but her dislike of her surroundings. What he is not picking up – and could not possibly at that stage – is that the character sitting next to him will prove to be his nemesis.

We are introduced to the film’s other key character, Lorraine Minosa (Jan Sterling) – a sweet-sounding name for one of the sourest characters in the whole of Wilder’s work. Skilful dramatist that he is, Wilder not only uses the character’s appearance for dramatic exposition but to push the narrative a little further, just through one phrase she uses about her husband: ‘dumb cluck’. It’s an immediate revelation of her attitude: that he had it coming, and that she’s more angry than anxious. At this point Tatum goes a bit quiet, letting Lorraine disclose herself in her own words, obviously sizing her up, and picking up not only her exasperation at her husband but her dislike of her surroundings. What he is not picking up – and could not possibly at that stage – is that the character sitting next to him will prove to be his nemesis.

A Deputy Sheriff (Gene Evans) is dealing with the situation – and not very sensitively or sympathetically. If he’s the deputy Sheriff, what on earth is the Sheriff like? Wilder again is using cunning delaying tactics to add greater impact to the later introduction of the Sheriff, who will be drawn into Tatum’s plan and whose clear disreputableness will be the yardstick by which the lowness of the scheme will be judged and condemned. I’ve always thought Wilder was taking a great risk here in offering such an unflattering portrayal of the forces of law and order at a time when such subversive characterisations could have been construed as being un-American. Even the Hollywood censor, blind to the blistering criticism of other aspects of the film, was to be perturbed by the fact that no obvious punishment will be meted out to a figure like the Sheriff who seems irredeemably corrupt. But then, as we shall see, the film’s distribution of punishment and retribution will be very idiosyncratic.

A Deputy Sheriff (Gene Evans) is dealing with the situation – and not very sensitively or sympathetically. If he’s the deputy Sheriff, what on earth is the Sheriff like? Wilder again is using cunning delaying tactics to add greater impact to the later introduction of the Sheriff, who will be drawn into Tatum’s plan and whose clear disreputableness will be the yardstick by which the lowness of the scheme will be judged and condemned. I’ve always thought Wilder was taking a great risk here in offering such an unflattering portrayal of the forces of law and order at a time when such subversive characterisations could have been construed as being un-American. Even the Hollywood censor, blind to the blistering criticism of other aspects of the film, was to be perturbed by the fact that no obvious punishment will be meted out to a figure like the Sheriff who seems irredeemably corrupt. But then, as we shall see, the film’s distribution of punishment and retribution will be very idiosyncratic.

We are also introduced here to Leo Minosa’s father, Papa Minosa (John Berkes), who will turn out to be one of the few humane characters we will encounter in the entire film. Through him, we learn that Leo has been trapped for about 6 hours in the cave and is down about 200 to 300 feet. To this, another dimension is added: when the Deputy tries to get the Native Americans to go in after Leo, they won’t – for them it’s a sacred place that has been violated and they are afraid of ‘bad spirits’.

It is the longest time that Tatum has been out of the narrative. It’s not filmed as a point of view shot, but there is a sense that while the scene is playing, Tatum is watching, waiting, listening, taking it all in. It’s the moment when he hears about the ‘bad spirits’ and ‘the mountain of the Seven Vultures’ that something clicks and he gets out of the car: you can almost feel his blood quickening as he senses the stirrings of a story, the possibility of an angle. Nothing is going to keep him out of that cave – certainly not that boorish Deputy Sheriff.

A short scene with the Deputy is a sharp little cameo because it gives a positive thrust to Tatum’s aggression. We know Tatum’s motives for wanting to go into that cave are far from altruistic: the snap of violence when he snatches the torch shows how determined he is. At the same time we enjoy the way he puts down an unpleasant character, exposing the coward beneath the bully. There is something attractive as well as appalling about his audacity and arrogance. At this particular point he is cutting through obstructive bureaucracy, getting something done. One of the ironies here – and it is to gather uncomfortable momentum as the film progresses – is that Tatum’s behaviour attracts the gratitude and devotion of Leo’s father, who sees him as Leo’s saviour. ‘God bless you,’ he says to Tatum as he prepares to enter the cave: that sentiment will be given a vicious twist both by the ultimate outcome of Tatum’s involvement with Leo, and Wilder’s visual handling of it. And like the master dramatist he is, Wilder adds a final twist of the knife. ‘Tell him we’ll get him out, tell him not to worry,’ says Leo’s father, to which Lorraine adds, ‘Tell him we’ll have a big coming-out party and brass band.’ Her sarcasm is a measure of the anger and scorn she feels at her husband’s foolhardiness, but Wilder is also subliminally preparing the ground for the grotesque celebratory carnival that is about to form to greet Leo’s anticipated rescue. We are left with that telling visual contrast: Lorraine smoking – fuming, in fact – and Papa Minosa crossing himself in prayer, a gesture that reminds us of how this whole thing started, when Herbie came across Leo’s mother. As Tatum and Herbie enter that cave, Wilder is deepening the implications of his tale: are we entering a tale of rescue and redemption, or of selfishness and sacrilege?

‘The human interest story’: Herbie and Floyd Collins

Tatum leads the way: it’s clearly a master/pupil relationship now, with Tatum giving Herbie another lesson in journalistic behaviour and Wilder taking us closer to Tatum’s strategy. Many people trapped down a mine is a powerful story (Wilder might have been thinking of films like G.W.Pabst’s Kameradschaft or Carol Reed’s The Stars Look Down), but as Tatum demonstrated with his rattlesnake analogy, it’s even better when there’s just one: it gives the story ‘human interest’. (The original title of the film was ‘The Human Interest Story’ and an ironic phrase for someone who grows progressively dehumanised as the plan proceeds). There is a significant reference to Lindbergh here; Cecil B DeMille mentions him when he greets Gloria Swanson on the Paramount steps in Sunset Boulevard; and, six years later, Wilder was to make his most all-American film about Lindbergh’s solo cross-Atlantic flight, The Spirit of St Louis. But what brings Tatum up short (so much so that he momentarily stops at this point, forgetting the urgency of the rescue) is the example of Floyd Collins, the reporter who ‘crawled in for the story [about a cave-in] and crawled out with a Pulitzer Prize.’

Tatum leads the way: it’s clearly a master/pupil relationship now, with Tatum giving Herbie another lesson in journalistic behaviour and Wilder taking us closer to Tatum’s strategy. Many people trapped down a mine is a powerful story (Wilder might have been thinking of films like G.W.Pabst’s Kameradschaft or Carol Reed’s The Stars Look Down), but as Tatum demonstrated with his rattlesnake analogy, it’s even better when there’s just one: it gives the story ‘human interest’. (The original title of the film was ‘The Human Interest Story’ and an ironic phrase for someone who grows progressively dehumanised as the plan proceeds). There is a significant reference to Lindbergh here; Cecil B DeMille mentions him when he greets Gloria Swanson on the Paramount steps in Sunset Boulevard; and, six years later, Wilder was to make his most all-American film about Lindbergh’s solo cross-Atlantic flight, The Spirit of St Louis. But what brings Tatum up short (so much so that he momentarily stops at this point, forgetting the urgency of the rescue) is the example of Floyd Collins, the reporter who ‘crawled in for the story [about a cave-in] and crawled out with a Pulitzer Prize.’

The Floyd Collins story was basically the starting point for Ace in the Hole and had been suggested to Wilder by one of his co-writers, Walter Newman, at that time a young writer for radio whom Wilder had spotted, later to become a highly regarded screenwriter on such films as The Man with the Golden Arm (1955) and Cat Ballou (1965). At this point in the film, Tatum has latched on to the Floyd Collins story because a plan is formulating in his mind: the treacherous path inside the cave might actually be the pathway out of his stultifying existence at Albuquerque where he feels as if he’s being buried alive. ‘I don’t like the looks of it, Chuck,’ says Herbie, to which Tatum replies: ‘I don’t either, fan, but I like the odds.’ William Holden’s anti-hero in Stalag 17 (1953) will say much the same thing when he volunteers to smuggle the officer out of the prison camp: the risk is worth taking, because the rewards might be greater.

When Tatum asks Herbie to stay behind, the motive seems sound enough, but you can sense a deeper motive too: he wants this story to himself and he doesn’t want Herbie getting too close to his methods. Wilder’s use of the setting is very expressive here. The occasional rumblings and slippages of soil keep the dangers at the forefront of our mind, but Tatum’s meandering, labyrinthine progress is also a metaphor for the devious workings of his mind and perhaps also a portent that he might be getting into this deeper than he realises. He suspects it might be his way out of being buried alive in Albuquerque: he might actually be digging a hole for himself he can’t get out of.

His meeting with Leo quickly sets up their relationship. As played by Richard Benedict, Leo seems a perfectly ordinary man who has got himself into a jam. Tatum brings him a blanket, coffee, cigar – and hope, becoming visually from now on virtually his only link to the outside world. When Leo is fretting that he might be trapped overnight, Tatum replies: ‘They’ll do it as fast as they can, but they’ve got to do it right.’ The word ‘but’ is very important there: it’s Tatum’s little wedge in the argument, whereby he’s thinking that Leo will be rescued at his required pace. And it’s at this point that Leo introduces the supernatural element (‘I guess they didn’t want me to have it…the Indian dead’). In reaction shot here, Kirk Douglas in reaction shot here suggests that Tatum is not giving him his full attention – part of him is listening, but the other part is thinking of how this can be worked up into the story.

Even Leo is tickled by the thought of media attention – little realising that this will, in effect, condemn him to death. He talks about his fear, the wartime camaraderie he experience, and then starts singing ‘The Hut Sut Song’ – ‘Hut Sut Rawlson an the rillerah, and a brawla, brawla sooit’. This nonsense ditty, supposedly based on a Swedish folk song, was a big hit in 1941; featured in the film San Antonio; and is heard in the background, for example, in Fred Zinnemann’s Pearl Harbor drama, From Here to Eternity (1953) as a kind of marker of the period. It was called a national disease, a song that, once heard, will unfortunately stick in your head until the day you die. Small wonder it nearly causes another cave-in.

The song, however, has lifted Leo’s spirits: Tatum’s too. Contact has been made, a bond established: ironic given the fact that Tatum is intending to milk the situation for what he can get out of it; doubly so, because he becomes Leo’s friend and finds himself fatally compromised by doing so. Herbie is struck by Tatum’s cheerful mood as he comes away from the meeting with Leo. ‘What is the story?’ he asks, to which Tatum replies: ‘Big.’ That line always reminds me of the moment in Citizen Kane when Kane says: ‘If the headline is big enough, it makes the news big enough.’ Tatum has not only got Floyd Collins, but Floyd Collins with an angle. ‘It’s Floyd Collins with an angle,’ he muses. ‘King Tut in New Mexico; white man half buried by angry Indian spirits… Collins was buried alive for 18 days… if I had just one week.’ That is almost a giveaway to Herbie, and he has to backtrack quickly. ‘I don’t make things happen,’ he says, ‘all I do is write about them.’ That isn’t what he told Herbie in the car. He is about to embroider the truth. In the light of the preceding events, a shot of Papa Minosa – a personification of trust and honesty – at the cave entry is poignantly timed. Tatum can throw the Deputy’s torch back at him in a gesture of contempt and have our endorsement, but the old man’s trust will continue to be an implicit rebuke to Tatum’s deviousness.

The song, however, has lifted Leo’s spirits: Tatum’s too. Contact has been made, a bond established: ironic given the fact that Tatum is intending to milk the situation for what he can get out of it; doubly so, because he becomes Leo’s friend and finds himself fatally compromised by doing so. Herbie is struck by Tatum’s cheerful mood as he comes away from the meeting with Leo. ‘What is the story?’ he asks, to which Tatum replies: ‘Big.’ That line always reminds me of the moment in Citizen Kane when Kane says: ‘If the headline is big enough, it makes the news big enough.’ Tatum has not only got Floyd Collins, but Floyd Collins with an angle. ‘It’s Floyd Collins with an angle,’ he muses. ‘King Tut in New Mexico; white man half buried by angry Indian spirits… Collins was buried alive for 18 days… if I had just one week.’ That is almost a giveaway to Herbie, and he has to backtrack quickly. ‘I don’t make things happen,’ he says, ‘all I do is write about them.’ That isn’t what he told Herbie in the car. He is about to embroider the truth. In the light of the preceding events, a shot of Papa Minosa – a personification of trust and honesty – at the cave entry is poignantly timed. Tatum can throw the Deputy’s torch back at him in a gesture of contempt and have our endorsement, but the old man’s trust will continue to be an implicit rebuke to Tatum’s deviousness.

The importance of Lorraine (Jan Sterling)

Wilder adroitly picks up the pace now after the steady tempo of the cave sequence to reflect the urgency of the situation and Tatum’s expressed desire to get the rescue operation in motion. Nevertheless, we see how Tatum is still quite disconcerted by Lorraine’s seeming lack of wifely concern. She seems incapable of talking about her home or her situation in anything other than dull tones or without an edge of sarcasm or bitterness. Sometimes it seems to take even Tatum by surprise, partly no doubt because it doesn’t coincide with the story he is already composing in his own head, and partly perhaps because her cynicism is a little too close to his own for comfort. For all his expression of concern about Leo and the urgency of the situation, his first call is to his editor, Mr Boot about his front-page story: no question about Tatum’s priorities. Wilder’s only signal of Tatum’s possible uneasiness about that is his interesting body language around the phone. Firstly he moves to his right and closes the door to the room in which Mrs Minosa is praying: he doesn’t want her listening in to his exclusive story about the ‘Curse of the Mountain of the Seven Vultures’, which in turn implies his recognition that what he is doing is, to say the least, a bit unethical. And then he moves round in the other direction when he notices that Lorraine is watching him. That will make little difference as she is on to him already.

Wilder adroitly picks up the pace now after the steady tempo of the cave sequence to reflect the urgency of the situation and Tatum’s expressed desire to get the rescue operation in motion. Nevertheless, we see how Tatum is still quite disconcerted by Lorraine’s seeming lack of wifely concern. She seems incapable of talking about her home or her situation in anything other than dull tones or without an edge of sarcasm or bitterness. Sometimes it seems to take even Tatum by surprise, partly no doubt because it doesn’t coincide with the story he is already composing in his own head, and partly perhaps because her cynicism is a little too close to his own for comfort. For all his expression of concern about Leo and the urgency of the situation, his first call is to his editor, Mr Boot about his front-page story: no question about Tatum’s priorities. Wilder’s only signal of Tatum’s possible uneasiness about that is his interesting body language around the phone. Firstly he moves to his right and closes the door to the room in which Mrs Minosa is praying: he doesn’t want her listening in to his exclusive story about the ‘Curse of the Mountain of the Seven Vultures’, which in turn implies his recognition that what he is doing is, to say the least, a bit unethical. And then he moves round in the other direction when he notices that Lorraine is watching him. That will make little difference as she is on to him already.

There are two great shots when Lorraine wanders on to the porch with her apple. Herbie is offering to pay for the gas; Papa Minosa wouldn’t dream of charging. (Wilder is very good at plotting the moments when Herbie has to leave the narrative, to make his delayed recognition of Tatum’s deceit more plausible.) Then she looks back through the window at Tatum on the phone, smiles and bites into her apple. The ‘innocence’ of Papa Minosa is well and truly undercut: Lorraine, the Eve in this despoiled Eden, knows the score (as Hugo Friedhofer’s music slyly underlines). Cut back to Leo in his mountain-trap, with a lizard crawling across the walls of the cave. It’s a reminder of the physical reality and discomfort of his situation, all the more telling because it’s going to be a good thirty minutes before we see him again: it’s as if he’s almost literally forgotten by some of those above ground who see him only in terms of a golden opportunity. Equally disturbing perhaps, Wilder, in developing his narrative, makes the audience almost forget him also.

There are two great shots when Lorraine wanders on to the porch with her apple. Herbie is offering to pay for the gas; Papa Minosa wouldn’t dream of charging. (Wilder is very good at plotting the moments when Herbie has to leave the narrative, to make his delayed recognition of Tatum’s deceit more plausible.) Then she looks back through the window at Tatum on the phone, smiles and bites into her apple. The ‘innocence’ of Papa Minosa is well and truly undercut: Lorraine, the Eve in this despoiled Eden, knows the score (as Hugo Friedhofer’s music slyly underlines). Cut back to Leo in his mountain-trap, with a lizard crawling across the walls of the cave. It’s a reminder of the physical reality and discomfort of his situation, all the more telling because it’s going to be a good thirty minutes before we see him again: it’s as if he’s almost literally forgotten by some of those above ground who see him only in terms of a golden opportunity. Equally disturbing perhaps, Wilder, in developing his narrative, makes the audience almost forget him also.

It’s at this point in the film that Jan Sterling as Lorraine comes into her own. Wilder is setting up another suspense situation to keep our interest engaged; she’s packed and all ready to walk out, but the bus has not yet arrived. As she waits in the store with Tatum, we learn more about her background before meeting Leo, who has promised more than he delivered: she now wants out of the marriage. It’s the kind of characterisation that has sometimes led to accusations of misogyny in Wilder’s work: for example, Barbara Stanwyck’s murderous femme fatale in Double Indemnity, or the gold-digging ex-wife in The Fortune Cookie (1966), who sees through the scam but who, like Lorraine, will return to her immobilised husband when she senses there’s money in it. Yet Lorraine earns our grudging respect in one regard at least: she’s the one character in the film who can give as good as she gets when dealing with Tatum. ‘Yesterday you never even heard of Leo,’ she sneers, ‘now you can’t know enough about him. Aren’t you sweet?’ Tatum is clearly a bit taken aback by that; that’s just a bit too close to the truth for his liking. And Lorraine is reminding us that Wilder’s heroes are hardly more admirable than his heroines. I’ve always thought his films less consciously misogynistic than comprehensively misanthropic.

At this time in her career married to the actor Paul Douglas, Sterling had first come to screen prominence with her role in the prison drama Caged (1948). She was later to be nominated for an Oscar for her performance in The High and the Mighty (1954), but it is Ace in the Hole where we see her at her best, for this is a fearless, truthful performance of a character who could on the surface just come over as an unfeeling monster. Sterling herself thought her character was not unsympathetic but was acting as she did out of a deep unhappiness at a marriage that had failed to deliver on its promise and whose future looked bleak but for this unexpected development. This is not unlike Tatum, in fact, and she is not slow to point this out. She turns the tables on him when he is expressing his disgust at the timing of her desertion of Leo. ‘Nice kid,’ he says, scornfully, to which she replies: ‘Look who’s talking….Honey, you like those rocks just as much as I do.’ One again one can see from Tatum’s reaction that the point has struck home.

‘There’s three of us buried here’

The following sequence has always seemed to me an absolute master-class in screen writing and direction. The situation has been set up beautifully. We know the characters now; why Lorraine wants to leave; and why Tatum wants her to stay to add to the ‘human interest’ angle of his story. But what can he do to stop her boarding the bus that will her away? Cue the arrival of the Federbers (Frank Cady and Geraldine Hall) who have read about the story in the paper and have come to visit the site. Tatum comes out to join them and Wilder frames all four – hypocritical instigator, embittered deserter, morbid general public in the same frame. Wilder now cuts to a closer shot of Tatum and Lorraine as they both seem to grasp the significance of this arrival – when Tatum describes his relationship to Leo as ‘friend’, the word seems both ironic and sinister. ‘Wake up the kids,’ says Federber, ‘they should see this. This is very instructive.’ Off they drive to stake their claim to the best spot, as if they were attending a show – as it soon will be. In the meantime, Tatum makes one last pitch to Lorraine, his gestures becoming a little more violent to reflect his determination. (His inner violence will become less controlled as the film draws on and lead finally to his downfall.) There’s no pretence here, no appealing to emotion or sentiment: it’s entirely to do with what’s in it for them. ‘There’s three of us buried here’ he tells her, ‘only I’m going back in style.’ With a last crack about how they must have bleached her brains as well as her hair, Tatum returns to the store.

The following sequence has always seemed to me an absolute master-class in screen writing and direction. The situation has been set up beautifully. We know the characters now; why Lorraine wants to leave; and why Tatum wants her to stay to add to the ‘human interest’ angle of his story. But what can he do to stop her boarding the bus that will her away? Cue the arrival of the Federbers (Frank Cady and Geraldine Hall) who have read about the story in the paper and have come to visit the site. Tatum comes out to join them and Wilder frames all four – hypocritical instigator, embittered deserter, morbid general public in the same frame. Wilder now cuts to a closer shot of Tatum and Lorraine as they both seem to grasp the significance of this arrival – when Tatum describes his relationship to Leo as ‘friend’, the word seems both ironic and sinister. ‘Wake up the kids,’ says Federber, ‘they should see this. This is very instructive.’ Off they drive to stake their claim to the best spot, as if they were attending a show – as it soon will be. In the meantime, Tatum makes one last pitch to Lorraine, his gestures becoming a little more violent to reflect his determination. (His inner violence will become less controlled as the film draws on and lead finally to his downfall.) There’s no pretence here, no appealing to emotion or sentiment: it’s entirely to do with what’s in it for them. ‘There’s three of us buried here’ he tells her, ‘only I’m going back in style.’ With a last crack about how they must have bleached her brains as well as her hair, Tatum returns to the store.

Having laid it all out, Wilder can now let the camera do the rest. Lorraine stands still, like the camera, but, as we hear the bus approach, she backs away slightly, suggesting a tiny weakening of resolve. Bus stops, blocking our view, adding to the suspense, then moves off and out of frame, like a horizontal wipe. Camera stares implacably as Lorraine walks back to the store, Tatum in long shot opening the door, the two now accomplices more than antagonists, the closed door sealing the bargain.

Having laid it all out, Wilder can now let the camera do the rest. Lorraine stands still, like the camera, but, as we hear the bus approach, she backs away slightly, suggesting a tiny weakening of resolve. Bus stops, blocking our view, adding to the suspense, then moves off and out of frame, like a horizontal wipe. Camera stares implacably as Lorraine walks back to the store, Tatum in long shot opening the door, the two now accomplices more than antagonists, the closed door sealing the bargain.

When Herbie returns later that morning, we can see that Escudero is coming alive, something adroitly underlined by Hugo Friedhofer’s score, which won a prize at that year’s Venice Film Festival as the score of the year and seems to me flawless and alert throughout in conveying atmosphere, momentum and connecting musical tissue. A supreme musical arranger for Erich Korngold and Max Steiner, Friedhofer had begun writing his scores in the 1940s, winning an Oscar for his magnificent score for William Wyler’s The Best Years of our Lives (which Wilder, incidentally, thought was the best directed film he’d ever seen and which was the first film score ever to be receive an extended analysis in a classical music magazine). According to the composer, Wilder was disappointed the score had no themes, to which Friedhofer replied: ‘Would you want me to soften the blow?’ Certainly Wilder is not softening anything here. Lorraine has immediately slapped an entry charge for anyone driving to the mountain; the carnival is beginning.

Tatum’s conversation with the doctor about Leo’s state of health has a sub-text that we see, but the doctor doesn’t: on the surface, solicitous, but underneath he’s checking on his investment. Herbie’s growing excitement at the way the story has developed is well conveyed by Bob Arthur. ‘You like it now, don’t you?’ says Tatum, to which Herbie replies: ‘Well, everybody likes a break. We didn’t make it happen.’ That’s the second time Herbie has quoted Tatum’s words back at him (remember ‘Cagey,eh?) and there’s a momentary double-take from Tatum, finely observed in Douglas’s performance: it could suggest his recognition that Herbie is on his side, but also a subliminal apprehension that these words might come back to haunt him. News of the sheriff’s arrival and his displeasure clearly doesn’t faze him, however: indeed he is ready for the next phase of his plan.

Dissolve to rattlesnake in a box, which cues in the appearance of the Sheriff, played by veteran heavy Ray Teal: the combination of those two things leaves us in no doubt how we are meant to view this character. Lorraine’s pointed disrespect seems entirely justified. Enter Tatum who is now ready to play his next hand, what he will call his ‘ace in the hole’ and explain how extending Leo’s entrapment for publicity purposes could be to the benefit of both of them. Tatum knows who he’s dealing with and is under no illusion that the sheriff’s re-election would serve anyone’s best interests other than their own. His opinion of the sheriff is conveyed in a gesture – he drops his cigarette in the sheriff’s drink.

Wilder is soon to bring into play two other crucial characters in this scene, Lorraine and Mr Smollett, the construction contractor. But before that, Tatum answers the sheriff’s query about what’s in it for him. ‘This is my story,’ he says. ‘I want to keep it mine.’ It’s striking how Wilder and Douglas play that line. It’s not said directly to the sheriff, it’s said more to himself, like that similar moment in Boot’s office; and it goes to the root of his motivation. This is not about money per se, this is his route back to self-esteem, recognition, his revenge on those back in New York who had put the boot in when he was down. There’s a neat bit of dramatic structuring at this point. The construction contractor, Mr Smollett (Frank Jaquett), has entered and, in calling for a coffee, he will bring Lorraine over to the table: she is to hear what passes between them and recognise what Tatum is up to. Smollett seems a decent working man and at first does not grasp the significance of Tatum’s question of how long the rescue operation is going to take. He asks the question twice and then cues in the sheriff with an almost imperceptible nod of the head, at which point the sheriff’s ‘HOW LONG?’ resounds as a threat. When Tatum suggests on health and safety grounds that they should drill an entrance from the top of the mountain and Smollett protests that that would take six or seven days, the sheriff is not slow to point out the consequences for him if he doesn’t do as he’s told: ‘You were a truck driver, now you’re a contractor, do you want to be a truck driver again?’ Tatum seals the bargain by attempting to assuage Smollett’s fears and sweetening his coffee (‘Sugar?’). You can’t help but be reminded of Lorraine’s rebuke to Tatum about his sudden interest in Leo – ‘Aren’t you sweet?’ So it’s appropriate then for Wilder at the end of the scene to move over to Lorraine at her till, able to change a $50 bill (which one suspects has not been a common occurrence in her life at the trading post) and watching Tatum move into a more comfortable room that has been vacated by Leo’s grateful father. Her look will carry us forward to the next scene – one of the most disturbing of the film.

When Tatum enters the room, one of the first things he notices are the two bottles that Herbie has brought for him and he’s vigorously rejected. It’s a temptation that must be resisted because his drinking got him in trouble in the past; and one of the later signs that things are beginning to unravel is the moment he starts drinking again. Enter Lorraine. Wilder can’t dislike the character that much, for he gives her some of his best lines. ‘I met a lot of hard-boiled eggs in my life,’ she tells him, ‘but you, you’re twenty minutes.’ We’re in film noir territory here. The hero’s face is in shadow, to suggest his shady schemes; and the heroine is a blonde siren turned on both by the money and by Tatum’s dynamism, even if it is at her husband’s expense. Disturbingly at this moment, she has never looked prettier, more alive: perversely, this is what Tatum can do to people, even decent ones like Herbie. Things are more exciting around him; he makes things happen. Lorraine makes a play for him; his response is to slap her across the face. That slap is shocking, much more so than Jimmy Cagney’s famous grapefruit in Mae Clarke’s face in Public Enemy. After all, Clarke was grumbling: here Lorraine has been anticipating a romantic embrace. To use a movie analogy, it’s like a brutal director getting the expression he wants from an unwilling actress to fit his conception of the role; and Tatum may be lashing out because he sees in Lorraine’s greed and ruthlessness something of himself, and he doesn’t like what he sees.

The big carnival: misery into spectacle

Three days have passed and, as we hear the voice of a radio broadcaster (Bob Bumpas), we can deduce that Leo’s predicament has become a media event. Indeed the disaster site now looks more like a drive-in, complete with cars parked in orderly rows, entrance fee, and even kiosks that sell hot dogs and popcorn. Wilder is developing a dark allegory of the morbidity of the film audience that might in some ways be said to anticipate Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954). A superb aerial shot from the top of the mountain discloses what the commentator calls this ‘new community’ that has sprung up. The cameraman on the film, Charles Lang Jr was one of Hollywood’s greatest and one of Wilder’s favourites, having previously worked with him on A Foreign Affair (1948) and later to photograph Sabrina (1954) and Some like it Hot. Intriguing and ironic that one of Wilder’s visually most spectacular films is at the same time one of Hollywood’s most corrosive attacks on the media’s capacity to turn human misery into visual spectacle.

Human morbidity surfaces in the interview with the increasingly appalling Mr Federber, who Tatum has earlier described as ‘Mr America’. His children are wearing Indian head-dress and licking an ice cream, and there are balloons in the background. Some pretty vigorous merchandising is obviously in full swing whilst Leo is trapped below. Federber is keener to insist that he and his wife were first on the scene than worry about Leo’s welfare, and he isn’t slow to advertise his business in insurance, a man who takes no risks, in other words, in contrast to Tatum (and an artist like Wilder).

When Tatum sees Lorraine and suggests she attends a special service that is being performed for Leo’s benefit, she retorts; ‘I don’t go to church. Kneeling bags my nylons.’ Wilder always credited his wife with that line; it catches the character to perfection. ‘Another thing, mister,’ she adds. ‘Don’t ever slap me again.’ Originally Wilder had added another line to that: ‘I might get to like it’. He cut it, possibly because it hinted at a sado-masochistic dimension to their relationship that would have been too daring for the times (it would have certainly have been in contrast to her relationship with weak and uxorious Leo). As it stands, the line has a different inflection: it’s a warning from a woman who won’t be pushed around – and it’s an omen.

When Tatum sees Lorraine and suggests she attends a special service that is being performed for Leo’s benefit, she retorts; ‘I don’t go to church. Kneeling bags my nylons.’ Wilder always credited his wife with that line; it catches the character to perfection. ‘Another thing, mister,’ she adds. ‘Don’t ever slap me again.’ Originally Wilder had added another line to that: ‘I might get to like it’. He cut it, possibly because it hinted at a sado-masochistic dimension to their relationship that would have been too daring for the times (it would have certainly have been in contrast to her relationship with weak and uxorious Leo). As it stands, the line has a different inflection: it’s a warning from a woman who won’t be pushed around – and it’s an omen.

The following brief scene in the car between Tatum and Herbie (and one notices that the admission charge to the mountain has doubled since we last saw it) is a reminder of the earlier car scene in the film just before the story broke, and offers a nice contrast. Herbie was a bit dubious about Tatum before: now he is completely under his spell. ‘Isn’t anything you can do wrong as far as I’m concerned,’ he tells Tatum, who seems slightly to back away from that: he doesn’t want anyone that close. Incidentally Tatum has changed his top from his striking black shirt, and this is the day his fortunes are to change also – and not entirely for the better.

The scene in the press tent serves as a reminder that Wilder himself was a journalist in Berlin before turning to screenwriting (and before the political situation in Nazi Europe prompted him to flee Berlin. Germany in 1933 was, as he put it, ‘not a place for a nice Jewish boy to be.’). It seems less press tent than bear pit, each man snarling his desires. Wilder was to revisit the press pack in The Front Page (1974), and they are no more sympathetically presented there. Kirk Douglas always felt that this was one of the reasons why the film got unfavourable reviews. As he put it in his autobiography, The Ragman’s Son, ‘critics love to criticize but they don’t like being criticized.’ Enter Tatum. This is payback time and how he relishes being able to turn the tables on his journalist colleagues. When one of them attempts to plead collegiality and says that they’re all buddies and all in the same boat, he replies with pointed relish: ‘I’m in the boat, you’re in the water.’ As he indicates when he displays his badge, he has the law on his side (he has it in his pocket as well). And just before he leaves to see Leo (this gloating has made him a bit late for his usual visit), he drops the news that he has quit his job but retains exclusive rights to this story and is open to the highest bidder.

The scene in the press tent serves as a reminder that Wilder himself was a journalist in Berlin before turning to screenwriting (and before the political situation in Nazi Europe prompted him to flee Berlin. Germany in 1933 was, as he put it, ‘not a place for a nice Jewish boy to be.’). It seems less press tent than bear pit, each man snarling his desires. Wilder was to revisit the press pack in The Front Page (1974), and they are no more sympathetically presented there. Kirk Douglas always felt that this was one of the reasons why the film got unfavourable reviews. As he put it in his autobiography, The Ragman’s Son, ‘critics love to criticize but they don’t like being criticized.’ Enter Tatum. This is payback time and how he relishes being able to turn the tables on his journalist colleagues. When one of them attempts to plead collegiality and says that they’re all buddies and all in the same boat, he replies with pointed relish: ‘I’m in the boat, you’re in the water.’ As he indicates when he displays his badge, he has the law on his side (he has it in his pocket as well). And just before he leaves to see Leo (this gloating has made him a bit late for his usual visit), he drops the news that he has quit his job but retains exclusive rights to this story and is open to the highest bidder.

Yet even Tatum is taken aback by the sight of the ‘Re-Elect Sheriff Kretzer’ banner draped across the mountain. Even by the sheriff’s standards that’s a bit blatant and seems to draw attention to the mountainous proportions of the deception. Tatum is now a media star and consents to a brief interview with the radio reporter, though, as he says, with unconscious irony: ‘Every second counts.’ Tatum is the one who has extended this situation for his own benefit so there’s more than a little hypocrisy here; but what he doesn’t realise is that time is running out. And he pauses on his return to the cave when someone in the crowd, a Mr Cusack queries the rescue methods, Wilder emphasising the tension of the moment by moving into close-up to show Tatum and Smollett momentarily in uneasy complicity, before Smollett gets the nod from Tatum to get back to work while he handles this. A woman’s inappropriate intervention breaks the tension and lets them off the hook; and then Tatum, like the gambler that he is, takes a risk, betting successfully that Mr Cusack’s recommended method of rescue was not successful in the case he remembered. The danger passes, but it’s been a tense moment. We see Tatum giving the gullible crowd a wave before entering the cave – it’s an anticipation of William Holden’s cheery farewell wave to the fellow prisoners he despises in Stalag 17 before disappearing down the escape tunnel.

Yet even Tatum is taken aback by the sight of the ‘Re-Elect Sheriff Kretzer’ banner draped across the mountain. Even by the sheriff’s standards that’s a bit blatant and seems to draw attention to the mountainous proportions of the deception. Tatum is now a media star and consents to a brief interview with the radio reporter, though, as he says, with unconscious irony: ‘Every second counts.’ Tatum is the one who has extended this situation for his own benefit so there’s more than a little hypocrisy here; but what he doesn’t realise is that time is running out. And he pauses on his return to the cave when someone in the crowd, a Mr Cusack queries the rescue methods, Wilder emphasising the tension of the moment by moving into close-up to show Tatum and Smollett momentarily in uneasy complicity, before Smollett gets the nod from Tatum to get back to work while he handles this. A woman’s inappropriate intervention breaks the tension and lets them off the hook; and then Tatum, like the gambler that he is, takes a risk, betting successfully that Mr Cusack’s recommended method of rescue was not successful in the case he remembered. The danger passes, but it’s been a tense moment. We see Tatum giving the gullible crowd a wave before entering the cave – it’s an anticipation of William Holden’s cheery farewell wave to the fellow prisoners he despises in Stalag 17 before disappearing down the escape tunnel.

The cheer fades into the sound of the drill and we are in Leo’s world now. This is a great shot, because it’s a contrast and a shock. It’s the first time Leo has been seen in the film for a good thirty-five minutes. By delaying this reappearance, Wilder has ensured that we have almost forgotten him as well as the crowd above and we might feel a bit guilty. His deterioration is alarming, and the pounding of the drill is understandably shredding his nerves. ‘I can’t stand it,’ he says, ‘it’s enough to wake the dead.’ The line is a reminder of Leo’s original feeling that this is some kind of punishment for defiling an Indian burial-ground. There is also the almost obsessive use now of the word ‘friend’, which during the film has become progressively devalued (remember Lorraine’s disdainful look when Tatum has described himself to the Federbers as Leo’s ‘friend’; or the sheriff’s phrase ‘friend of the family’ to the other journalists to defend his ploy of giving Tatum exclusive access to Leo). The word is assuming ominous overtones and making Tatum feel a bit queasy. Like Tatum’s second scene with Herbie in the car, his second scene with Leo is distinctly different from the first. Tatum seems less sure of himself: no rallying sing-song here. Leo’s reference to his imminent fifth wedding anniversary is significant, for it will bring things to a crisis. This dismal scene has been ironically prefaced by Tatum’s cheery wave to the crowd; Wilder brutally rounds it off by cutting from Leo’s ‘She’s so pretty’ to a shot of Lorraine, in bright sunshine in contrast to Leo’s gloom, actually looking quite pretty. Leo’s absence is doing her good. The carnival is arriving. When Papa Minosa is protesting, she barely bothers to make eye-contact with him: she’s too busy counting in the trucks and calculating the profits. A siren announces the appearance in their press car of Tatum with Herbie. Kirk Douglas’s performance here eloquently conveys that his encounter with Leo has left him shaken. His response to Lorraine’s ‘Means everything’s going to be fine, doesn’t it, Mr Tatum?’ is a look of utter distaste at her lack of genuine concern, but not far removed either, one surmises, from a barely suppressed self-disgust.

The cheer fades into the sound of the drill and we are in Leo’s world now. This is a great shot, because it’s a contrast and a shock. It’s the first time Leo has been seen in the film for a good thirty-five minutes. By delaying this reappearance, Wilder has ensured that we have almost forgotten him as well as the crowd above and we might feel a bit guilty. His deterioration is alarming, and the pounding of the drill is understandably shredding his nerves. ‘I can’t stand it,’ he says, ‘it’s enough to wake the dead.’ The line is a reminder of Leo’s original feeling that this is some kind of punishment for defiling an Indian burial-ground. There is also the almost obsessive use now of the word ‘friend’, which during the film has become progressively devalued (remember Lorraine’s disdainful look when Tatum has described himself to the Federbers as Leo’s ‘friend’; or the sheriff’s phrase ‘friend of the family’ to the other journalists to defend his ploy of giving Tatum exclusive access to Leo). The word is assuming ominous overtones and making Tatum feel a bit queasy. Like Tatum’s second scene with Herbie in the car, his second scene with Leo is distinctly different from the first. Tatum seems less sure of himself: no rallying sing-song here. Leo’s reference to his imminent fifth wedding anniversary is significant, for it will bring things to a crisis. This dismal scene has been ironically prefaced by Tatum’s cheery wave to the crowd; Wilder brutally rounds it off by cutting from Leo’s ‘She’s so pretty’ to a shot of Lorraine, in bright sunshine in contrast to Leo’s gloom, actually looking quite pretty. Leo’s absence is doing her good. The carnival is arriving. When Papa Minosa is protesting, she barely bothers to make eye-contact with him: she’s too busy counting in the trucks and calculating the profits. A siren announces the appearance in their press car of Tatum with Herbie. Kirk Douglas’s performance here eloquently conveys that his encounter with Leo has left him shaken. His response to Lorraine’s ‘Means everything’s going to be fine, doesn’t it, Mr Tatum?’ is a look of utter distaste at her lack of genuine concern, but not far removed either, one surmises, from a barely suppressed self-disgust.

That feeling is to be carried forward into the next scene, modifying his ostensible triumph, nagging away at him like an aching tooth. There’s another window shot from inside the trading post, but in complete contrast to the one earlier when Herbie had stopped for gas. Now the room is teeming with people, a measure of the success of Tatum’s scheme. Yet when he enters his room, there is a strong sense that he’s still troubled by his meeting with Leo. A sign of that uneasiness is his taking the bottle, but hesitating still to pour a drink. It’s at that point, when his conscience is beginning to bother him, that Boot appears again – the very symbol of journalistic probity – and Tatum takes a drink almost in defiance. What will follow is an argument about journalistic ethics but also, to some degree, about old and new, about honest reporting as opposed to sensationalism to promote sales. Pointing to Tatum’s deputy sheriff star, Boot recognises that he has bought his exclusive coverage as part of a deal to get the sheriff re-elected. We know, of course, that’s only half the story; and Tatum seems a bit relieved he doesn’t know more. The phone will punctuate the argument at key points, with big-city editors bidding for his services and with Tatum waiting for the one call that will justify what he’s done – the call from New York.

When he tells Boot he has resigned from the Albuquerque paper, Boot’s reaction is one of regret. ‘I’m sorry to hear that, Chuck,’ he says. It’s the first time he’s called him ‘Chuck’ in the film and the sorrow feels genuine: partly because he thinks Tatum is a good reporter; and partly because he thinks he’s going in the wrong direction. Tatum raises the subject of that embroidered sign again and Boot takes it as a sign that it still troubles him, but Tatum brushes this aside. What he doesn’t brush aside is the moment when Boot wonders whether there is anyone buried down there at all. ‘Yes, there is,’ Tatum replies, grimly. ‘I’ve made sure of that.’ It’s a terrific line and marvellously framed and acted. When he says it, Tatum has his back to Boot – he doesn’t want him to see his expression – but the comment is almost made to himself as an accusation, the one thing about this situation that is making him uneasy. It’s also an answer to a criticism that is sometimes made of the film: that Wilder doesn’t create a strong enough antagonist to challenge Tatum and that the film suffers dramatically as a result. In fact, Wilder’s heroes are very often their own best antagonists, well aware of the dubiousness of what they are doing and wondering at what point they might feel they’ve gone too far.

Herbie’s entrance causes a distinct increase in tension, because, if Tatum is a lost cause, Boot thinks, Herbie isn’t: which way will he jump? At that particular moment Tatum does look a much more exciting and charismatic example and prospect than Boot. There is a particularly fine shot when all three of them are in the frame at the point where Tatum gets his all-important third call, this time from New York, as it brings all the tensions in the air to a point of crisis. Porter Hall’s performance here is terrific, as Boot never takes his eyes off Herbie, staring probingly like a stern father; for his part, Herbie won’t look at him. ‘He wants to be going, going,’ says Tatum about Herbie’s future, to which Boot replies, pointedly: ‘Going where?’ He exits, hat slightly awry, a physical sign of his emotional discomposure. Tatum dismisses him with a little nod of the head – Kirk Douglas’s head movements throughout the film are incredibly expressive, incidentally – but then deals with some relish with his old boss, Nagel.

Herbie’s entrance causes a distinct increase in tension, because, if Tatum is a lost cause, Boot thinks, Herbie isn’t: which way will he jump? At that particular moment Tatum does look a much more exciting and charismatic example and prospect than Boot. There is a particularly fine shot when all three of them are in the frame at the point where Tatum gets his all-important third call, this time from New York, as it brings all the tensions in the air to a point of crisis. Porter Hall’s performance here is terrific, as Boot never takes his eyes off Herbie, staring probingly like a stern father; for his part, Herbie won’t look at him. ‘He wants to be going, going,’ says Tatum about Herbie’s future, to which Boot replies, pointedly: ‘Going where?’ He exits, hat slightly awry, a physical sign of his emotional discomposure. Tatum dismisses him with a little nod of the head – Kirk Douglas’s head movements throughout the film are incredibly expressive, incidentally – but then deals with some relish with his old boss, Nagel.