by NEIL SINYARD

Readers of this short article will be forgiven if their initial response is: “Frank who?” And if they then consult a variety of respected reference sources (e.g. Halliwell, Katz, the BFI’s screenonline website, Robert Murphy’s edited anthology of British and Irish directors, Brian McFarlane’s epic Encyclopaedia of British Cinema) they will be none the wiser, for he is not mentioned in any of them. A BFI Film Forever source cites a Frank Nesbitt who was born in Chicago in 1938 and died in 1990, but he seems to be simply the namesake of the director with whom we are concerned, who was born in South Shields on 27 June 1932 and died in Los Angeles at the age of 74. He directed three feature films in the 1960s and early 1970s whilst he was still in his thirties, but then, to the best of my knowledge, never made another film.

Readers of this short article will be forgiven if their initial response is: “Frank who?” And if they then consult a variety of respected reference sources (e.g. Halliwell, Katz, the BFI’s screenonline website, Robert Murphy’s edited anthology of British and Irish directors, Brian McFarlane’s epic Encyclopaedia of British Cinema) they will be none the wiser, for he is not mentioned in any of them. A BFI Film Forever source cites a Frank Nesbitt who was born in Chicago in 1938 and died in 1990, but he seems to be simply the namesake of the director with whom we are concerned, who was born in South Shields on 27 June 1932 and died in Los Angeles at the age of 74. He directed three feature films in the 1960s and early 1970s whilst he was still in his thirties, but then, to the best of my knowledge, never made another film.

My curiosity in him was piqued when I was researching the career of Carol White for a booklet I was writing for the Network blu-ray release of John Mackenzie’s film Made (1972). I had never seen Frank Nesbitt’s film, Dulcima (1971), in which White co-starred with John Mills and which was considered good enough to be a British entry at the Berlin Film Festival. There is no reference to it in the BFI’s critical anthology, Seventies British Cinema (2008). Gill Plain’s fine study of John Mills’s career in her book, John Mills and British Cinema (2006) contains no reference to Dulcima either, although it seems to me (having now caught up with the film) one of the finest character performances of the actor’s later career. Curiously, Mills’s own autobiography, Up in the Clouds, Gentlemen Please does not mention it.1 Perhaps he thought the subject was a little too close to home: he plays a middle-aged man who falls in love with a woman who is thirty years younger than he is; that same year his daughter Hayley, without her father’s full approval, was marrying a man 33 years her senior, the producer/director Roy Boulting.

Dulcima had been one of the projects undertaken by Bryan Forbes during his brief and ill-fated tenure as head of EMI film production; and in his autobiography, A Divided Life, Forbes described the two leading performances as “beautifully judged”. Unfortunately he spelled the name of the director incorrectly and omitted him from the index. Forbes was distressed that the film did not receive the appreciation he felt it deserved. This was partly due, he felt, to poor marketing and distribution. Also the reviews tended to be lukewarm. “It’s neat, but nothing,” opined Time Out, in the kind of dismissive review that can destroy an artist’s soul. Could the poor commercial return and the dismal critical response to his film have been the factors which disillusioned Nesbitt with the film industry?

During the 1960s, he had made a short, Search for Oil in Nigeria (1960), and been an assistant director on such films as Terence Fisher’s The Horror of it All (1964) and John Gilling’s The Brigand of Kandahar (1965). He had also directed two British B-movies, Walk a Tightrope (1963) and Do You Know this Voice? (1964), both of which starred that estimable Hollywood heavy, Dan Duryea. Steve Rogers of Network distributors (who, to their credit, have released all three Nesbitt features on dvd) described these films to me as “belonging to the bizarre sub-genre of fading American stars in weird British b-movies.” “Bizarre” and “weird” they are, but also absorbing and well crafted.

In Walk a Tightrope, Duryea plays a dock-worker, Carl Lutcher, with a propensity to violence, living a precarious and unfulfilled existence with his devoted girl-friend (Shirley Cameron). “You know something?” he tells her, “I hate people.” From what we are to learn about his childhood, his period in a mental institution and his treatment in a coroner’s court, he has every reason to do so. What has triggered it in this particular instance, however, is that he has carried out a hit on a London architect, Jason Shepperd (Terence Cooper) at the behest, and in the presence, of Shepperd’s wife, Ellen (Patricia Owens), only for her to react hysterically to her husband’s murder. When Lutcher demands that she pay the remaining money she promised, she strenuously denies agreeing to any such arrangement. Unbeknown to both of them, Shepperd’s best friend, Doug (Richard Leech), who was in the house at the time of the shooting and had been knocked out, has regained consciousness sufficiently to overhear the exchange between wife and killer before Lutcher makes good his escape. He is appalled by what he has heard: what can it mean? Doug is later persuaded by Ellen that she is telling the truth and reassured by her determination to catch the killer of her husband, to whom she had been married for only six months and to whom she seemed utterly devoted. “Yes, get him,” she says. “I’d give my soul.” With her assistance, the police will apprehend Lutcher and he will be tried in a coroner’s court. Whilst admitting to the murder, the accused still insists (and despite the absence of any obvious motive on the wife’s part) that Mrs Shepperd had hired him to kill her husband. When she denies this on oath and the court accepts her testimony over his, he can only retort: “May you rot in hell!” For the benefit of readers who might wish to see the film for themselves, I will not disclose the surprise twist. Suffice to say, that although some viewers might well have solved the mystery before the end, I was completely taken in and did not see it coming.

According to the film’s publicity, Walk a Tightrope was shot in ten days and edited in six. If so, it is quite an achievement, because it looks a proficient piece of film-making. For a B-movie, its technical credentials are impressive. The effective photography and score are by seasoned professionals, Basil Emmott and Buxton Orr, respectively. The screenplay is by the experienced film and television writer, Mann Rubin, who is probably best known for his screenplays for Hollywood movies such as The Best of Everything (1959), Warning Shot (1966) and the Frank Sinatra thriller, The First Deadly Sin (1980). The co-starring of Patricia Owens opposite Dan Duryea also adds a touch of quality, for she would have been a familiar presence to regular cinema audiences of the time, having appeared in a number of popular and prestigious Hollywood movies of the late 1950s, including Sayonara, No Down Payment and Island in the Sun (all 1957), not to mention possibly her most memorable film role in the horror classic, The Fly (1958) and her appearance in my favourite John Sturges western, The Law and Jake Wade (1958). She was also directed by Alfred Hitchcock in an episode from his tv series Alfred Hitchcock Presents entitled ‘The Crystal Trench’ (1959), which had a plot that seems somewhat similar to that of the recent British film, 45 Years (2015). Stardom seemed to beckon, but it never quite materialised, and she was to retire from the screen in 1968. Here she gives deceptive depth to a character who is not quite what she seems; and she more than holds her own in the courtroom scenes with Duryea, even when sporting headgear intended to signify mourning but which looks more like a lamp-shade than a hat. The character might seem demure on the surface, but, when someone says to her, “You didn’t hate me that much”, Owens delivers an answering look of such withering hostility that it credibly causes the man to retreat from the room. It is one of those performances that works well enough on one seeing, but, on a second viewing, and with full knowledge of the final narrative twist, gains an added layer of surprise and conviction.

The same could be said for Frank Nesbitt’s direction, where certain plot moments are given emphasis in a way that makes perfect sense in narrative terms on a first viewing but accrue additional significance with hindsight. The early scenes of pursuit and the scene in the café when the heroine is unexpectedly greeted by her husband and his best friend are an illustration of this. The shock moments – Duryea suddenly bursting into their home, or the moment when he surprises the heroine in the pub when she is beginning to suspect he might not be coming – are particularly well delivered. Modest in means it may be, but, as a supporting feature (and as a feature directing debut), Walk a Tightrope is a cut above average.

The production company that made Walk a Tightrope, Parrock-McCallum (i.e. Jack Parsons and Neil McCallum) was also responsible the following year for Do You Know This Voice?, adapted by McCallum from a 1960 novel by the esteemed American thriller writer, Evelyn Berckman. The kidnapping of a schoolboy for ransom goes horribly wrong when the boy is accidentally killed (offscreen) by one of the kidnappers, who nevertheless presses ahead with his claim for ransom in the hope that the parents will pay up before the body is discovered. Unlike in the novel, where the identity of the kidnappers is not disclosed until halfway through, in the film we are quickly made aware of the guilty party. He is a hospital orderly, John Hopta (Dan Duryea), an American who has remained in England after the war and who has committed the crime in league with his English wife, Jackie (Gwen Watford). The police have no clues, apart from the testimony of an old Italian lady, Mrs Marotta (Isa Miranda), who happens to be the Hoptas’ next-door neighbour and on friendly terms with the husband. She was outside the phone-box when the final call for ransom was being made. Because she was retrieving coins that she had dropped on the ground, she did not get a good look at the caller’s face, but there was something about the feet and the shoes that had struck her as not quite right and she thinks she will be able to remember more in time. The police have recorded the phone call with the ransom demand and broadcast it in the hope that someone will recognise the voice. In the meantime, Mrs Marotta has set herself up as bait by letting the press know that she caught a glimpse of the killer and could recognise him if she saw him again.

Having set up the characters and situation very concisely, Nesbitt now contrives a number of neat suspense sequences that follow from a strikingly-angled, noir-ish shot of Duryea in his home, as he muses that “I’ll have to kill her. The little old lady knows.” The murder attempts are not without a vein of black humour, as if Nesbitt has absorbed some of the strategies of Mackendick’s The Ladykillers (1955) and Crichton’s The Battle of the Sexes (1960). On the first occasion, Hopta’s attempt to silence the little old lady is thwarted by the whistle of a boiling kettle, causing Mrs Marotta to swerve abruptly out of the range of Hopta’s noose: a murder averted by the prospect of a cup of tea. (A cup of tea will also play an important role in the unmasking of the kidnappers in one of the film’s final scenes.) In a second attempt, Hopta will steal out of his house at the crack of dawn to slip some poison into Mrs Marotta’s bottle of milk on her doorstep. (Those were the days when the local milkman delivered milk on your doorstep as part of his morning round.) Yet this will also be thwarted during a tense scene round the kitchen table with Mrs Marotta, Hopta and a young policeman who has been sent to protect her, for the first creature to sample the milk will be the hapless family cat, Bruno, who will promptly collapse and die. The final murder attempt is without any comic diversion. Hopta has broken into her house wearing a stocking mask over his face. The large alternating close-ups when he confronts Mrs Marotta in the kitchen unnervingly convey both the threat he represents and the overwhelming fear she feels.

The film is competently acted, but also interestingly characterised. Duryea’s character is a variation on the part he played in Walk the Tightrope: an embittered misanthrope who feels that life has consistently dealt him a bad hand, forcing him finally to resort to crime. He shows little sign of remorse for the death he has caused: indeed he even suggests he might have done the boy a favour. “He’s better off than the rest of us,” he says. “He died when he was clean and innocent.” He has wrongly assumed that, because the boy went to an expensive school, the parents must be rich, which is not the case, so the plan seems doomed from the outset. That usually serene actress, Gwen Watford is unexpectedly intense here, strongly and even poignantly suggesting the anguish of a wife who has lived for years with a man she loves but who senses an aura of failure about him that could frustrate their last attempt at some sort of freedom and happiness. As the old lady, Isa Miranda sensitively conveys the personality of a warm-hearted and courageous woman who still feels something of an outsider in a foreign land. There are fine performances also from Alan Edwards and Shirley Cameron as the boy’s parents, expressing the depth of their grief in completely different ways. And incidentally, whatever happened to Shirley Cameron? She gives sympathetic, contrasting performances in both these films, but seems to have done nothing afterwards on screen.

I would like to put in a word here also for Canadian born actor, Neil McCallum, who died at the age of only 46 in 1976 and who, if he is mentioned at all in reference books on British cinema, is briefly referred to as a beefy, burly actor who appeared in tough-guy roles in films such as The Siege of Pinchgut (1959) and The War Lover (1962). (The latter is the film the heroine of Walk a Tightrope has gone to see when she is being followed by the villain: a nice in-joke.) McCallum has a small acting role in Walk a Tightrope as a prosecuting counsel; but, as these two Nesbitt films remind us, he was not simply a reliable supporting actor but a talented producer and screenwriter as well. His screenplay for Do You Know This Voice? is an excellent adaptation that, in several respects, seems to me a distinct improvement on its source. At the simplest level, he has transposed the action from America to England; changed the nationality of the old lady from Czechoslovakian to Italian; and streamlined the narrative, eliminating a number of characters and a redundant subplot involving an unconvincing affair between the police officer who is investigating the case and the old lady’s daughter-in-law. Skilfully, he has turned one of the weakest points of the novel (the coincidence of the person outside the phone box just happening to the kidnapper’s next-door neighbour) into a moment of fateful dramatic irony, for, in the film, it is Hopta who has suggested that Mrs Marotta call her niece and even given her some coins for that purpose, an act of kindness that will account for her presence outside the phone box and unwittingly bring about his own downfall. (I am reminded of what that great screenwriter William Rose said was the main theme of The Ladykillers: “In the Worst of All Men there is a little bit of Good – that will destroy them.”) The friendship between Hopta and the old lady adds an extra dimension of complexity to the drama. Whereas in the novel the husband-and-wife kidnappers are irredeemably nasty and villainous, in the film they are more desperate than evil and have a genuine devotion to each other, which gives the twist at the end a sadness which far transcends that of the finale of the novel. It is a clever script that, with all the other elements, helps to make the film a decidedly superior slice of British film noir.

Adapted by Nesbitt from a 1953 novella by H.E,Bates, and finely photographed entirely on location in colour by Tony Imi, Dulcima tells the story of a young country girl of that name (Carol White), who seeks an escape from a life of drudgery at home by becoming housekeeper and then occasional lover of a middle-aged farmer, Mr Parker (John Mills), whom she has first encountered in a drunken heap outside his cottage and discovered a pile of money hidden in his hat. As she improves his living surroundings, he becomes more and more attached to her; and she keeps him at arm’s length for part of the time by inventing a boyfriend called “Albert”, who, she says, might disapprove strongly of their relationship. As the novella puts it: “Albert came gradually forward into the situation not simply as a third party but as a watchful and terrifying eye keeping guard on her.” The situation becomes more complicated when she meets and falls for a young gamekeeper (Stuart Wilson), whom Parker assumes is the “Albert” she has mentioned. Parker proposes marriage; but when he sees Dulcima and the gamekeeper together, he will be consumed by jealousy, and things will end will an unexpected eruption of violence. Bates described his novella as “ a tragedy of the underdeveloped”.

Nesbitt’s adaptation keeps fairly close to the original, with some judicious additions and modifications. He elaborates on the novella’s market scenes, not simply for local colour but for crucial motivation, since it is Dulcima’s observation of Parker’s low cunning in getting the best deals for himself on these occasions that provides her with the justification for her own deceptions. Nesbitt’s depiction of her home life is grim enough to account for her migration to Mr Parker’s and her determination to milk the situation for what it is worth, even if it involves a few sexual favours along the way. For a time the story chugs along with the earthy hedonistic humour that television audiences would later see as characteristic of H.E. Bates in his Darling Buds of May mode. Yet Nesbitt plants a few clues early on that developments in this central relationship, where genuine affection contends with secret greed and dishonesty, could take an ominous turn. In fact, at one stage when she exaggerates the farmer’s anger if he sees the gamekeeper encroaching on his land, Dulcima unwittingly predicts the tragic outcome.

It is hard to imagine how the two leading performances could have been bettered. Carol White is marvellous at suggesting the unease lurking beneath the surface of the heroine’s duplicity and for conveying the dilemma of an essentially kind-hearted person, who does not wish to hurt Mr Parker but is torn between her desire to escape rural poverty and the new romantic feelings stirring in her for the gamekeeper. John Mills is particularly fine in the last part of the film, when his fear of losing Dulcima leads to a frightening explosion of drunken rage as he confronts her and then wrecks the living room they have built up together and tears up the wedding dress he has bought for her. Nesbitt’s imaginative addition to the novella’s ending (unlike in Bates’s story, Dulcima has decided to stay with Mr Parker rather than leave) makes it even more ironic and painful..

Taking the three films together, one would not claim Nesbitt to be a particularly distinctive stylist. He knows how to tell a story; and he knows how to get good results from his actors and technicians. Just occasionally he can be guilty of labouring a point (e.g. the use of animal imagery to suggest Parker’s lusting after the heroine in Dulcima or the over-emphatic shot of the poisoned glass in Do You Know This Voice?), but he can deliver shock effects in his films, of which there are a few, with impressive force. Shoes are important in all three films, but one would hesitate to build an auteurist case out of that.

Yet there is one thing that particularly struck me as consistent about all three films and marked them out as being bold and unusual in mainstream cinema: they all end unhappily, and in rather similar ways. In all of them, a main character is left at the end in a state of complete mental collapse. All three films are about schemes which go awry, and where the wrong people get caught up in the crossfire of desire and deceit. In all of them there is an innocent victim who is killed. None of them has a redeeming love story; and although all involve crime of one sort or another, the forces of law are either ineffectual or invisible. In the two films that are adaptations, Nesbitt adds twists that are not in the originals but give an extra touch of blighted fortune to the fates of torn and tormented main characters who are seeking salvation from a miserable domestic and social situation. All three films afford the characters a tantalising glimpse of a better future, but then disaster strikes just at the point when things seem finally okay and they can move forward. “It’s all over.” says Gwen Watford’s wife in relief at the end of Do You Know This Voice?: alas, she speaks more truly than she knows. What a strangely pessimistic and intriguing portfolio of work: was the pessimism somehow prophetic? When talking about Dulcima in his autobiography, Bryan Forbes described Frank Nesbitt as a “young director starting out on a career” who, he wrote, “showed great promise in his handling of this melodramatic bucolic tale.” Promise? Starting out? We know now that Nesbitt was not starting out on a directing career but packing up; and one would love to know why.

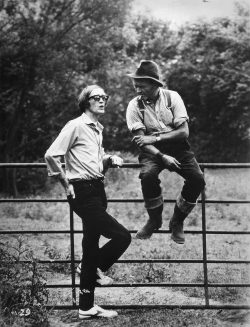

Thanks to Network DVD for providing us with the image of Frank Nesbitt and John Mills at the top of this article.

All three Nesbitt films are available from Network DVD: Do You Know This Voice?, Walk a Tightrope and Dulcima.

Updated edition, 2001. ↩