by NEIL SINYARD

The following is a slightly edited transcript of the audio commentary I gave for the Criterion Classics DVD release of Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole. (I was also interviewed about the film on the Masters of Cinema DVD/blu ray release.) This essay will probably make more sense if you have viewed the film recently. I’ve kept the relatively informal style and hope the commentary will be of interest. For a number of reasons, personal and artistic, no director has been more important to me than Billy Wilder.

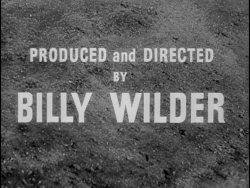

Plain credits on a parched, soil surface: Ace in the Hole announces itself immediately as a gritty film featuring characters with hearts of stone. The name that dominates the credits is writer/producer/director Billy Wilder; and Ace in the Hole (1951) is following on from such hard-hitting Wilder movies as Double Indemnity in 1944, The Lost Weekend in 1945 and Sunset Boulevard in 1950 which shone a harsh spotlight on unsavoury aspects of American life. Like other acclaimed writer-directors of the 1940s in Hollywood, such as Preston Sturges, John Huston and Joseph L.Mankiewicz, Wilder had become a director to protect his own scripts. ‘It isn’t important that a director knows how to write,’ he would say, ‘but it is important that he knows how to read.’

Plain credits on a parched, soil surface: Ace in the Hole announces itself immediately as a gritty film featuring characters with hearts of stone. The name that dominates the credits is writer/producer/director Billy Wilder; and Ace in the Hole (1951) is following on from such hard-hitting Wilder movies as Double Indemnity in 1944, The Lost Weekend in 1945 and Sunset Boulevard in 1950 which shone a harsh spotlight on unsavoury aspects of American life. Like other acclaimed writer-directors of the 1940s in Hollywood, such as Preston Sturges, John Huston and Joseph L.Mankiewicz, Wilder had become a director to protect his own scripts. ‘It isn’t important that a director knows how to write,’ he would say, ‘but it is important that he knows how to read.’

‘Tell the Truth’: Enter Chuck Tatum

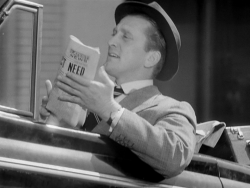

Wilder was very adroit at giving his main characters memorable entrances – think of Marilyn Monroe’s first entry as Sugar Kane in Some like it Hot (1959) where she gets a wolf whistle from a train – and Kirk Douglas’s first appearance as Chuck Tatum, as he is towed into Albuquerque, is appropriately unorthodox here. Wilder is establishing three things very quickly: that Tatum is down on his luck; that he is nevertheless good at exploiting even adverse situations to his advantage, so he gives the appearance of being chauffeured into town; and also that he is interested in newspapers – and looking around for the next angle or opportunity.