by NEIL SINYARD

Charlie Chaplin’s autobiography was one of the publishing sensations of the decade when it appeared in 1964. He had been encouraged to write it by Graham Greene and some of the story was already well known; yet critics were taken aback by the quality of the writing and particularly by the painful and powerful evocation of his childhood, which made such an impression that just the childhood section of the book was later published as a separate work in its own right. Alistair Cooke spoke for many when he noted what he called ‘an eerie similarity between the first sixty pages of Chaplin’s Autobiography and Oliver Twist.’ And he went on: ‘As a reincarnation of everything spry and inquisitive and Cockney shrewd and invincibly alive and cunning, Chaplin was the young Dickens in the flesh’.1

Chaplin as the reincarnation of Dickens is an interesting thought. There is no doubt in my mind that Dickens was the most pronounced artistic influence on Chaplin’s career. He had discovered Dickens before he could even read and even the origins of his showbiz career owed a lot to Dickens. Growing up in London, Chaplin had seen the actor Bransby Williams imitating Dickens characters like Uriah Heep, Bill Sykes and the old man in The Old Curiosity Shop and it had ignited a love of the theatre and a fascination with literature. ‘I wanted to know what was this immured mystery that lay hidden in books,’ he wrote, ‘these sepia Dickens characters that moved in such a strange Cruickshankian world. Although I could hardly read, I eventually bought a copy of Oliver Twist.’2 He was so enthralled with these Dickens characters that he began imitating Bransby Williams imitating them; and it was then that he was discovered and invited to make his stage debut. What is particularly intriguing about this is that Dickens as a boy used to console himself in the same way by impersonating favourite characters from novels he had read (particularly those of Fielding) and that his early ambition was a career on stage. To the end of his life he was a frustrated actor, liking nothing better than giving public readings of his description of the murder of Nancy in Oliver Twist and then enquiring politely how many women in the audience had fainted.

In my view, Chaplin was to the 20th century what Dickens was to the 19th: both centuries unthinkable without them; both men comic/poetic dramatists of quite unparalleled popularity who used satire, caricature and suspense to assault injustice. They were both artistic giants in their respective fields, but fascinatingly, giants in remarkably similar ways and for remarkably similar reasons. The parallels between their lives and personalities as well as their work are quite uncanny:

Physically they were quite similar: both small and wiry.

Temperamentally they were very alike: as a close friend of Chaplin’s, Thomas Burke remarked, they were both ‘querulous, self-centred, moody insecure men who, with all their success, remained vaguely dissatisfied with life.’3 In both cases, this dissatisfaction lay rooted in a traumatic childhood never entirely exorcised but which permeated every aspect of their life and art. ‘Even now,’ said Dickens in his later years, ‘famous and caressed and happy, I forget in my dreams that I have a dear wife and children; even that I am a man; and wander desolately back to that time of my life’.4 Chaplin too: ‘I’ve known humiliation,’ he said, ‘and humiliation is a thing you never forget. Poverty- the degradation and helplessness of it! I can’t feel myself any different, at heart, from the unhappy and defeated men, the failures.’5

Perhaps because of their similarly traumatic childhoods (Dickens haunted by family debts, the threat of prison and his period in the blacking factory, Chaplin buffeted between workhouse and orphanage because of an absent father and a mentally unstable mother) they are made precociously aware of life’s misfortunes, and, in response to this, they are similarly drawn to images of innocence in their work and lives, an innocence that they themselves have missed. One thinks of Dickens, in his work, with those child-women heroines, like Dora in his most autobiographical novel, David Copperfield, or Little Dorrit, who seems to stay little, however old she gets, and, in his life, his association with Ellen Ternan when he’s 45 and she’s 18 which leads to his separation from his wife. Chaplin too, with his four marriages to teenage brides, culminating in his marriage to Oona O’Neill (daughter of the great playwright Eugene O’Neill), when he’s 54 and she’s 18, a marriage that actually turned out to be an extremely happy one. Their attitudes to women and their depiction of heroines seem to be a mixture of adoration and misogyny, deriving from mother figures whom they loved but by whom they also felt in some way betrayed. For example, in Dickens’s case, when all the debts had been repaid and the family reunited, his mother had suggested that perhaps young Charles could remain at the blacking factory which he so hated rather than find some schooling; it is said that Dickens never quite forgave her for that. Similarly, Chaplin’s love for his mother was always mixed with a frustration and anger at her mental illness, an anguish that she’d not been able to protect him from a premature awareness of the harshness of the world (his father had abandoned the family when Charlie was seven).

Similarly their popularity was quite unprecedented and it’s interesting that when Chaplin’s popularity was being discussed in the 1920s and 30s, Dickens was often invoked as a comparison. I always loved the story concerning Dickens’ popularity which extended to a situation where, when British ships were coming into New York harbour, they were receiving frantic signals from the shore saying ‘How is little Nell?’ When Chaplin visited London in February,1931 for the premiere of City Lights, The Times wrote: ‘Dickens knew something of popular enthusiasm, but could he have beheld the press of people gathered…in honour of Mr Chaplin, he might have rubbed his eyes in astonishment.’6 It is said that, during one visit to London, Chaplin received 73,000 fan letters from the capital alone. His popularity was such that it became something of a psychopathological phenomenon, notably on an occasion on 12 November 1916 when Chaplin was allegedly spotted in 800 places at the same time.

Their popularity cut across cultures, countries and class, and it might have delayed proper critical recognition of their stature, for in both cases their artistic reputations plummeted for a while after their deaths. Henry James thought Dickens superficial as later did F.R. Leavis (though he changed his mind in time for the centenary of Dickens’s death): and George Henry Lewes was moved to observe that there probably never was a writer of so vast a popularity whose genius was so little appreciated by the critics. Still if the critics had their reservations about Dickens, they weren’t shared by his peers and fellow novelists, such as Thackeray, Joyce, Conrad, Kafka and Dostoyevsky, who said that what kept him sane during his exile in Siberia was reading Pickwick Papers and David Copperfield. Similarly, if the critics really went for Chaplin after his death, calling his films old-fashioned, technically unadventurous and woefully sentimental, their reservations weren’t shared by his peers and successors, such as Buster Keaton, Jean Renoir, Woody Allen, Francois Truffaut, Jean-luc Godard, and Federico Fellini, for whom Chaplin was ‘the Adam from we’re all descended’. There was a nice comment from Sean French when he heard Barry Norman claim that Chaplin was over-rated: ‘I felt as if a molehill had said that Mount Everest’s reputation for height was undeserved.’

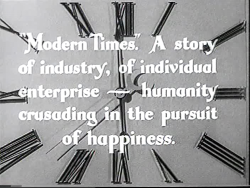

There are couple of extracts from Chaplin’s movies that I now wish to examine for what I see as their Dickensian characteristics. The first is an extract from Chaplin’s 1936 film, Modern Times, and the Dickens comparison I have in mind is his novel, Hard Times. It was published in 1851 and is one of his most terse, polemical works, particularly its savage critique of a Utilitarian approach to education, which prioritises Fact over Imagination and which sees children as potential economic units rather than as individuals whose innate creativity also needs to be nurtured and encouraged. (This might strike you as rather topical.) But another great theme of the novel is Industrialisation and the relation of men and women to machines and how this industrial drive, unless harnessed to some kind of humanity, could result in the depersonalisation/mechanisation of the individual. The industrial town in Hard Times is appropriately called Coketown, as if it is smothering and suffocating its inhabitants; and there is a great passage in the novel (the opening of Chapter X1 entitled ‘No Way Out’) about the industrial workplace and the relation of man to the machine, written in a style that wonderfully parodies the educational system he is also attacking: it’s satirically statistical:

So many hundred hands in this Mill; so many hundred horse Steam Power. It is known, to the force of a single pound weight, what the engine will do; but not all the calculators of the National Debt can tell me the capacity for good or evil, for love or hatred, for patriotism or discontent, for the decomposition of virtue into vice, or the reverse, at any single moment in the soul of one of these, its quiet servants, with the composed faces and the regulated actions. There is no mystery in it; there is an unfathomable mystery in the meanest of them, for ever.-

I think that’s one of the great passages in Dickens. He’s not idealising humanity (he’s careful to balance ‘good’ OR ‘evil’, ‘love’ OR ‘hatred’ etc.) but he’s still recognising and cherishing the rich complexity of humanity, even in – perhaps especially in – what he calls the ‘soul… of its quiet servants’. He goes on: ‘There is no mystery in it [i.e. the engine, the machine]; there is a mystery in the meanest of them, for ever.’ I’m sure Chaplin would have responded to that. When his silent features were re-released during the sound era and he added a commentary, he would refer to the Tramp as ‘The Little Fellow’- and was heavily attacked for his so-called ‘condescension’- but what he was thinking of, I believe, in that phrase was precisely the equivalent of Dickens’s ‘the meanest of them’, those people who are up against it, whom society marginalizes and whom governments sometimes do not even acknowledge as a statistic, but in whom (both Dickens and Chaplin would insist) there is still a mystery and depth that deserve recognition. The Tramp is the kind of figure Society would ignore or even disdain, but, as James Agee asserted in his classic essay on silent film comedy, ‘Comedy’s Greatest Era’, the Tramp character in Chaplin’s hands was ‘as centrally representative of humanity, and as many-sided and mysterious as Hamlet’.7 In Modern Times, the Tramp is an assembly-line worker who is being driven progressively mad by the repetitive routine of his job. In an early sequence in the film, an inventor has visited the plant with his revolutionary contraption: an automatic feeding-machine that will eliminate the lunch-hour (and hence accelerate production and maximise worker efficiency) by feeding the worker whilst he continues to work at his job. The manager is impressed but insists that the machine be tried out on one of the workers. Inevitably the Tramp is chosen for the demonstration, and chaos ensues, with the contraption attacking the man before self-destructing.

Reviewing the film at the time, Graham Greene thought that that was the best scene Chaplin had ever done; and, with typical scrupulousness, he described it as ‘horrifyingly funny’. Greene rarely used adverbs so his use of ‘horrifyingly’ there is doubly striking: he recognises the human horror behind the comic conceit. The scene is essentially about the depersonalisation of the individual; and whereas the breakdown of the machine is comical, the kind of managerial strategy it exemplifies is not, and could lead to human breakdown – which in the film it does.

I think you’ll see from what I’ve said about Hard Times and Modern Times that another similarity that Dickens and Chaplin shared was their social and political outlook; and indeed it has been discussed in very similar terms by the critics. Both of them have been described and even derided as sentimental radicals who were not great political thinkers or men of ideas and who advocated a change of heart more than a change of system. Carlyle was quite disdainful about Dickens’s political ideas: ‘He thinks men ought to be buttered up, and the world made soft and accommodating for them, and all sorts of fellows have turkey for their Christmas dinner.’ Curiously, when Modern Times was re-released in 1972, George Melly in The Observer wrote about Chaplin in very similar terms: ‘He’s always been appalled by inhumanity but has nothing to propose beyond mere kindness. His dream is petit-bourgeois: a chicken in the pot, grapes against the wall.’ Still, in an unjust, intolerant and oppressive society, even basic decency can sound menacing. Lenin might have been appalled by what he called Dickens’s bourgeois sentiment, but Tolstoy wasn’t; and George Bernard Shaw said that Little Dorrit alone had converted him to Socialism. George Melly might have found Chaplin’s social ideas ‘petit-bourgeois’, but they were deemed sufficiently subversive to prompt the FBI to open a file on him in 1922 that eventually ran for around 2,000 pages and which subsequently led to his exile from America for 20 years.

When discussing the social ideas of Dickens, George Orwell was critical of those kindly benefactor figures, like Brownlow in Oliver Twist or Jarndyce in Bleak House, who help without dirtying their fingernails, as it were, or without doing anything to question the basic fabric of their society. As Orwell said, ‘Even Dickens must have reflected occasionally that anyone who was so anxious to give his money away would never have acquired it in the first place.’ But clearly Dickens did reflect on this: there’s that sardonic comment in Hard Times, when Gradgrind’s mean-spiritedness is encapsulated by his thought that ‘the Good Samaritan was a bad economist’: and in Great Expectations, Dickens will take the whole idea of the legacy and the benefactor to grotesque tragic-comic extremes. Similarly Chaplin, in one of his greatest films, City Lights, does his own brilliant variation on the benefactor theme when the Tramp, who has rescued a millionaire from drowning and is showered with money by the man when he’s drunk but treated with contempt when the man is sober, uses the money to finance the eye operation of a blind flower-seller, with whom he has fallen in love but who has deduced he is a gentleman. Like Magwitch in Great Expectations, he will wind up in prison (the millionaire will accuse him of theft); but when he comes out and passes the flower-shop in utter destitution he notices that the flower-girl can now see; and she, intrigued by this tramp figure who seems so interested in her, invites him in. It’s when they touch that she realises who her benefactor is; and it really is like the moment when Pip slowly recognises that his benefactor is the convict Magwitch and can barely conceal his dismay. If you know City Lights, you will never have forgotten the ending: when the flower-girl says, ‘You?’, and the film closes on one of the greatest close-ups in film history: the Tramp’s face at the point of recognition- apologetic, apprehensive, smiling his delight that she can see, but, unnervingly, through her reaction, also seeing himself.

So how do you change or improve society so that children are properly housed and fed and all people have the chance to fulfil their potential? Both Dickens and Chaplin were preoccupied with this question. Both of them shrank from the thought of Revolution. When the Tramp finds himself at the head of a Communist rally in Modern Times, he is so entirely by accident (though it is an ominous foretaste of the political accusations that were to be made against him in the following decades). And if you think of the Dickens of A Tale of Two Cities and his ambivalence about the French Revolution and the violent overthrow of tyranny: it was the best of times but it was also the worst of times. As he put it, ‘the aristocrats deserved all they got but the passion engendered in the people by misery and starvation replaced one set of oppressors by another.’

A key issue in both Dickens and Chaplin is essentially: how do you prevent power from being abused? The ferocity of their social attack is directed not so much at the law-breakers as the law administrators. In Oliver Twist, for example, Fagin and Co. are certainly crooks but Dickens shows them more sympathy than he shows for the workhouse authorities. (Fagin was actually named after Dickens’s best friend at the blacking-factory, Bob Fagin, which suggests that in Dickens’s eyes, for all his villainy and corruption, there are some redeeming features in that character. Incidentally, David Lean’s film catches this brilliantly in just one detail after Oliver has been taken into Fagin’s lair by the Artful Dodger and Fagin is jokily demonstrating how to pick pockets, and Oliver starts to laugh: and it’s a really strange high-pitched sound and it startles even him- and you suddenly realise that this must be the first time the little lad will have laughed in his entire life.) Fagin and Co are criminals but they’re not hypocrites. Dickens reserves his most savage indignation and irony for those who perpetuate cruelty and injustice in the name of fairness and good: Bumble in Oliver Twist; the superficially self-made man Bounderby in Hard Times, of whom Dickens says ‘there was a moral infection of claptrap in him’; or the law in Bleak House, whose primary interest, says Dickens, is not in justice but in lining its own pockets or, to use his specific phrase, in ‘making business for itself.’ Chaplin’s Tramp also finds that his most persistent enemies are policemen, magistrates, the courts. There is no identification in Dickens and Chaplin between the forces of law and the forces of good: indeed in Great Expectations, Pip’s growing maturity is mainly signalled through his increasing sympathy with the ex-convict Magwitch, whom the law regards as an irredeemable criminal deserving to be hanged. In Chaplin too, the poor must, in every sense, help themselves. In Modern Times, which is a comedy but also a gruelling look at the effects of the Depression in 30s America (unemployment, followed by strikes, riots, police brutality, imprisonment – a not unfamiliar sequence of events) there’s a moment when the Tramp, who’s got a job at a department store as a night watchman, disturbs some robbers and recognises one of them as a friend he met when both were in prison. ‘We ain’t burglars,’ the friend says to him. ‘We’re hungry.’ In Chaplin’s eyes- and he would have learnt this as a child – theft is preferable to starvation. The crime is not in the act of stealing but in the cause of that necessity. And still on the subject of theft, starvation and justice, this is a diary entry of Dickens in May 1852: ‘Two little children whose heads scarcely reached the top of the desk were charged at Bow Street on the seventh with stealing a loaf out of a baker’s shop. They said in defence that they were starving, and their appearance showed that they were speaking the truth. They were sentenced to be whipped in the House of Correction. To be whipped! Woe, Woe! can the State devise no better sentence for its little children?’ And he underlines the following: ‘will it never sentence them to be taught?’ I have no doubt Chaplin would have cheered that sentiment. He was self-taught, and, in his autobiography, he writes: ‘I wanted to know, not for the love of knowledge but as a defence against the world’s contempt for the ignorant.’8

In the second film extract for discussion, I want to draw some connections between Chaplin’s film, The Kid, made in 1921 and Dickens’s Oliver Twist. It’s a film full of overt autobiography, and full of parallels to the Dickens novel. As mentioned earlier, Oliver Twist was the first book Chaplin ever read and it remained his favourite novel throughout his life. He would read it to his children, and it was the novel he was reading and re-reading, apparently, during the last year of his life, young Oliver’s experience in the orphanage approximating and reminding him of his childhood.

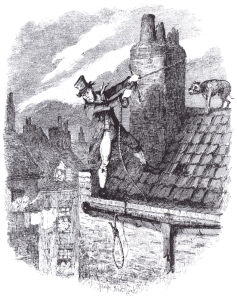

The Kid was Chaplin’s biggest artistic risk at that time. It was three times longer than any film he had previously made; it was expensive to make, the ratio of used film (i.e. that which is seen in the completed film) to unused film being 1:53, which was high even by Chaplin’s perfectionist standards. It also had two ingredients that had not been so overt before – pathos (the opening title reads, ‘a picture with a smile, and perhaps a tear’) and social criticism, directed at the way society treats its unfortunates, here an unmarried mother, a tramp who stumbles across an abandoned baby and after initial reluctance looks after it, and a kid with no socially sanctioned parents. Like Oliver Twist, it begins with the tragedy of the unmarried mother and the child abandoned to its fate. As it develops, the relationship between the Tramp and the kid becomes a genial variation on that between Fagin and the Artful Dodger as they go into business together: the kid will break people’s windows and five minutes later the Tramp will innocently come along to offer his services as a glazier. Also, in both The Kid and Oliver Twist, the big set-pieces are roof-top chases – in Dickens, to trap Bill Sikes after the murder of Nancy; and in Chaplin, the Tramp’s endeavour to rescue the little boy when he has been taken from him by the authorities. Prior to the sequence the little boy, played by Jackie Coogan, has been ill and the Tramp has sent for the doctor, which is when the trouble starts. As we will see, the authorities attempt to take the boy from the Tramp, who is roused to desperate measures to rescue the boy from a tragic fate.

[Extract starts at 31:42]

In David Robinson’s superb biography of Chaplin, he writes that the attic setting might be ‘an illustration to Oliver Twist, with its sloping ceiling, peeling walls, bare boards, maimed furniture…’but adds that is also an autobiographical recollection of the attic in Pownall terrace where Chaplin lived as a child and where he remembered that every time he sat up in bed, he bumped his head on the ceiling.’9 There are a number of significant points about that sequence:

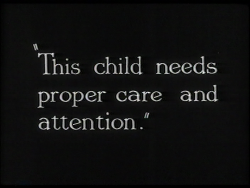

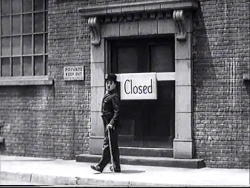

I would argue that even Chaplin’s use of the intertitles there is very Dickensian: that is, when a sequence is introduced with the title ‘The Proper Care and Attention’, it is fundamentally ironic and critical, because what we are about to see is anything but; and I think he picked that up from Dickens and Oliver Twist, for Dickens’ critique of the workhouse authorities very often takes that same sarcastic form: for example, when he refers to ‘juvenile offenders without the inconvenience of too much food or too much clothing’; or when he refers to Oliver’s ‘auspicious and comfortable surroundings’ when the boy has been thrown into a small dark room after being flogged for asking for ‘more’. What Dickens is doing is parodying the workhouse authorities’ own language, their own justification for their actions, and irony and parody can be particularly effective tools for exposing and emphasising hypocrisy. This is exactly what Chaplin does in The Kid. ‘Proper care and attention’ is the Doctor’s phrase and we see in reality what that means. The brusque music and the pompous manner of the authorities emphasise that they are acting out of simple officiousness rather than out of any sense of care. This was a very painful scene for Chaplin to film because it brought back all his childhood terror of officials like welfare workers, doctors, the police, as well as a specific incident when he was seven years old and brutally separated from his mother who was forced to move to Lambeth Workhouse whilst Chaplin and his half-brother Sydney were carted off to the Hanwell School for Orphans and Destitute Children.

The roof-top chase would have struck audiences at the time as an unusual sequence in a Chaplin movie. Chaplin as a rule didn’t like chase sequences and this was one of the reasons why he left the Mack Sennett organisation: ‘does everything have to end in a chase?’ he moaned. But this is a chase scene with a difference: the emphasis is not on slapstick but on suspense. Audiences would have recognised that sending the kid to the orphanage was a potential death sentence, and that’s emphasised by the way the kid is thrown into the back of the truck as if he were an animal on the way to the slaughterhouse.

When the Tramp and the kid are re-united, it is noticeable that they are both crying; and, as Jackie Coogan was later to say, ‘for audiences at the time, to see this great clown, this mischievous tramp really crying was a considerable shock.’ There was a tangle of emotions at play here. Prior to making this film, Chaplin’s first child, a boy, had been born malformed and died within three days; and the boy’s mother, Chaplin’s first wife, said later that one of the few things she remembered about their disastrous marriage was that ‘Charlie cried when the child died.’ During the making of The Kid, Chaplin had become very fond of little Jackie Coogan and, when preparing this scene, dreaded having to make the lad cry and called in the parents for help. ‘Leave it to me,’ said the dad, and apparently, said to the boy: ‘Look, you little runt, you do what Mr Chaplin wants or I’ll send you to the orphanage myself!’ In fact, Coogan was the best co-star Chaplin ever had, for two reasons: firstly, he worshipped Chaplin, which always helped; and also he was a brilliant mimic. As Coogan was to say later, the problem for Chaplin was always that he wanted to play all the parts himself and could probably play them all better than anyone else, so his idea of direction was to demonstrate to the actor what he wanted, in order for the actor then to imitate what he had demonstrated. That worked a treat with the five-year-old Coogan but it didn’t go down so well with, say, Marlon Brando (in Chaplin’s last film, The Countess of Hong Kong). The Kid was to make Coogan a big star, and the search was on for a vehicle that would exploit his talents. One might have guessed what would turn out to be his first big starring role: Oliver Twist.

The final thing I want to pick up on The Kid and its Dickensian quality is its mood, particularly evident in that scene: the pathos, the sentiment. Both Dickens and Chaplin have been likewise criticised for what has been described as their gross sentimentality. When he wants to wring your heart, Dickens assaults you with an armoury of Biblical effusions, most notoriously when describing the death of little Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop, about which Oscar Wilde famously said: ‘Only a heart of stone could read the death of little Nell without laughing.’ Chaplin pours on his own music, which is tender or treacly according to taste: e.g. ‘Smile, though your heart is breaking’ in Modern Times. How you respond to all this is very personal, but I always think that what’s behind it, the subconscious source of it, in both cases, is a kind of social revenge: they want to make society weep for having made them weep. And, in both cases, I don’t think the sentiment is ever cynically or externally applied: it’s fundamentally rooted in who they are. They can be maudlin and self-indulgent, but I would contend that they are never insincere. They are, after all, dealing upfront with the primary human emotions- hunger, fear, joy, envy, love, sadness- and I’m not sure understatement would be a lot of help there and might even induce complacency; and the thing I like most about their irony is not its wit but its anger. They were sophisticated in their art, but feeling was always as important as intellect, and sentiment as important as sophistication. The advice that Billy Wilder used to give to aspiring young screenwriters was: ‘Make the subtleties obvious’. That’s something I love in Dickens and Chaplin: they make their subtleties obvious. And I think what popular audiences responded to instinctively in both was that they sensed the authenticity behind the artistry: that Dickens’s social indignation is not manufactured, it arises out of bitter memory of early first-hand experience of social deprivation; and Chaplin’s Tramp, similarly, whilst a creation of his imagination, is also the sum of his observation as a child walking the streets of London and taking everything in. He always said that the Tramp’s walk was inspired by a beggar he saw who was walking in shoes too small for him but who couldn’t afford a new pair; and there’s a wonderful phrase by a local reporter in Chicago, Gene Morgan, who described interviewing Chaplin in his Tramp’s costume and said: ‘You can’t keep your eyes off his feet. Those big shoes are buttoned with 50 million eyes….’10

As they grew older, their work grew darker, to the dismay of many of their critics. In the case of Dickens, one Victorian critic, E.B. Hamley was representative of many when he wailed: ‘In the wilderness of Little Dorrit we sit down and weep when we remember thee, O Pickwick!’ Why aim to be profound when you can just be funny? And, of course, exactly the same criticism was levelled at Chaplin when he finally opened his mouth in the Talkies in The Great Dictator (1940) and Monsieur Verdoux (1947), for me two of his greatest films. So many critics complained: who wants to hear your political opinions when you have the gift of laughter? Yet a young François Truffaut, in his notoriously combative days as a critic for Cahiers du Cinema, had the answer to that when he reviewed a reissue of The Great Dictator in 1957: ‘I despise the set mind that rejects the ambitious from someone who’s supposed to be a comic….If Chaplin has been told that he is a poet or a philosopher, it’s because it’s true and he was right to believe what he heard. Without willing it or knowing it, he helped men live; later, when he became aware of it, would it not have been criminal to stop trying to help them even more?’11 Up until the middle of the last century, Dickens was always being accused of exaggeration, but the critic Lionel Trilling was one who thought that people who said that had no eyes or ears. ‘We who have seen Hitler, Goering, Goebbels on the stage of history,’ he wrote, ‘are in no position to suppose that Dickens exaggerated in the least the extravagance of madness, absurdity, malevolence in the world- or, conversely, when we consider the resistance to those qualities, the goodness.’12 And, of course, it was the Nazi threat in Europe which persuaded Chaplin finally to break his silence in the Talkies era and to make his anti-Fascist satire, The Great Dictator, exploiting surely the most bizarre resemblance of modern history (even to the extent of almost the same birth-date): that between Chaplin and Hitler. The great French critic André Bazin called it a settling of accounts: Chaplin’s revenge, he said, on Hitler’s double crime of elevating himself to a god and stealing Charlie’s moustache. The film is a funny but ferocious attack on totalitarianism, holding it up to ridicule in the noble, if perhaps forlorn, hope that the ensuing laughter would make it impossible for such a political philosophy ever to be taken seriously again. It did not work contemporaneously, but Milos Forman has since commented how spiritually liberating he found the film when he was allowed to see it after the end of the war.

Let me conclude on a note of speculation. What did Chaplin think Dickens would have made of the 20th century? And, if he had known him, what kind of moving death-bed scene might Dickens have contrived for Chaplin? Actually I can give the answer to the first question. A Birthday Dinner was given by the Dickens Fellowship at the Café Royal in London in 1955 in which Chaplin was Guest of Honour. Their choice of principal guest was very deliberate. Members of the Fellowship had asked themselves which great artist would best pay tribute to Dickens, and indeed who might Dickens himself have chosen for such an occasion. They came to the conclusion that the ideal person was Charlie Chaplin who, as the President of the Fellowship said, ‘was a great artist who, like Dickens, has shown a great interest in his fellow man and a profound concern at the direction in which the world was going.’ In his response, Chaplin ventured to suggest that, if he were alive today, Dickens would have been dismayed by many aspects of our western democracy: its hypocrisy and double-talk about peace and armaments; the paranoia of the cold war; by scientific irresponsibility about nuclear weapons; and would have called for a better balance between cleverness and kindness, intellect and feeling.13

If that was Chaplin’s tribute to Dickens, what might Dickens have reciprocated for Chaplin? Surely an emotional death-bed scene, in which a revered old man, surrounded by his devoted family, dies peacefully in his sleep. Oh yes, and as an extra touch: make it Christmas Day. And, of course, that is precisely what happened: Chaplin died on the Christmas Day of 1977. As well as the sentiment, though, Dickens, with his love of the macabre, might even have provided the slightly grotesque epilogue to this event: namely, that Chaplin’s coffin was later stolen by two pathetically incompetent kidnappers who demanded a ransom for its return but who were quickly caught and the coffin recovered.

Dickens and Chaplin – both artists of genius who preserved an unquenchable sympathy for society’s victims, and an equally unquenchable suspicion of society’s administrators and leaders, whom they fearlessly assailed with an inimitable blend of mockery and indignation in a ceaseless endeavour to reverse and rectify abuse and injustice. Both found and maintained their own equilibrium through a combination of comic and character observation so piercing that it forever embedded itself in the popular consciousness. They made singular contributions towards a recognition of their respective popular forms- the novel, the cinema- as genuine art forms, but both transcended even that, belonging not simply to literature and to film, but to history and to the air we all breathe. What Jacques Tati said of Chaplin is equally true of Dickens: ‘his work is always contemporary, yet always eternal.’

This is a slightly expanded version of a lecture given at the ‘Adapting Dickens’ Conference at de Montfort University on 27 February 2013.

Stephen Weissman, Chaplin: A Life (2009), p. 94. ↩

Charles Chaplin, My Autobiography (1964), p. 48. ↩

Robinson, p. 443. ↩

Quoted in James Wood’s review of Peter Ackroyd’s biography, Guardian, 6 September 1990. ↩

Louis Giannetti, Masters of the American Cinema (1981), p. 80. ↩

Simon Louvish, Chaplin: The Tramp’s Odyssey (2009), p. 245. ↩

James Agee, Agee on Film, p. 9. ↩

Chaplin, p. 134. ↩

David Robinson, Chaplin: His Life and Art (1985), pp. 253-4. ↩

Robinson, p. 136. ↩

François Truffaut, The Films in My Life (1978), p. 55. ↩

Quoted by Angus Calder in his Introduction to the Penguin edition of Great Expectations. ↩

The occasion is described in detail in The Dickensian, Summer,1955. ↩

Pingback: Aspects of Innocence and Experience: some reflections on literature and film analogy, with particular reference to Henry James and Billy Wilder | Neil Sinyard on Film