by NEIL SINYARD

Charlie Chaplin’s autobiography was one of the publishing sensations of the decade when it appeared in 1964. He had been encouraged to write it by Graham Greene and some of the story was already well known; yet critics were taken aback by the quality of the writing and particularly by the painful and powerful evocation of his childhood, which made such an impression that just the childhood section of the book was later published as a separate work in its own right. Alistair Cooke spoke for many when he noted what he called ‘an eerie similarity between the first sixty pages of Chaplin’s Autobiography and Oliver Twist.’ And he went on: ‘As a reincarnation of everything spry and inquisitive and Cockney shrewd and invincibly alive and cunning, Chaplin was the young Dickens in the flesh’.1

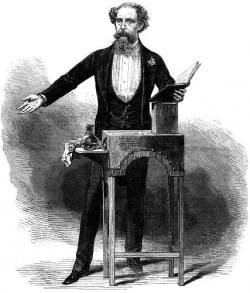

Chaplin as the reincarnation of Dickens is an interesting thought. There is no doubt in my mind that Dickens was the most pronounced artistic influence on Chaplin’s career. He had discovered Dickens before he could even read and even the origins of his showbiz career owed a lot to Dickens. Growing up in London, Chaplin had seen the actor Bransby Williams imitating Dickens characters like Uriah Heep, Bill Sykes and the old man in The Old Curiosity Shop and it had ignited a love of the theatre and a fascination with literature. ‘I wanted to know what was this immured mystery that lay hidden in books,’ he wrote, ‘these sepia Dickens characters that moved in such a strange Cruickshankian world. Although I could hardly read, I eventually bought a copy of Oliver Twist.’2 He was so enthralled with these Dickens characters that he began imitating Bransby Williams imitating them; and it was then that he was discovered and invited to make his stage debut. What is particularly intriguing about this is that Dickens as a boy used to console himself in the same way by impersonating favourite characters from novels he had read (particularly those of Fielding) and that his early ambition was a career on stage. To the end of his life he was a frustrated actor, liking nothing better than giving public readings of his description of the murder of Nancy in Oliver Twist and then enquiring politely how many women in the audience had fainted.