by NEIL SINYARD

The text that follows is an edited version of a lecture I gave some years ago to introduce a series of Ferens Fine Art lectures at the University of Hull on the topic of Post-Impressionism. The initial focus was on the first Post-Impressionist Exhibition in London in 1910, what it contained, and how the reaction to it was symptomatic of what was going on generally in the arts at this time. I have always thought that the period between roughly 1910 and 1914 was one of the most remarkable periods of creativity in the arts ever, and it was to be the topic of my PhD, but a book on Billy Wilder intervened; the thesis was never finished; and my career took a very different direction.

To begin with the quotation that provides the title of this essay, a famous quote from Virginia Woolf in an essay entitled ‘Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown’ published in 1924. “In or about December 1910,” she wrote, “human character changed.” Virginia Woolf was often deliberately playful and provocative in her artistic pronouncements; she was never, however, frivolous. The date she cited was carefully chosen: a conscious allusion to the first Post-Impressionist exhibition at the Grafton Gallery in London, which was the first extensive viewing that the public in England had been given of the work of artists such as Cezanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin and Picasso. The change in human character that Virginia Woolf was suggesting was not so much of a change of personality per se but a way of perceiving personality (1910 was also the year when Freud was giving a famous lecture on the origins and development of psychoanalysis) and also of the way of portraying character, in paint and in print. In the early years of the 20th century, artists in different fields were seeking a new language or mode of expression to render what the art critic Roger Fry called “the sensibilities of the modern outlook”.

It was Roger Fry who had organised the Exhibition, which had actually been opened to the press on November 5th (Virginia Woolf had allowed a little time for its impact to be felt). Needless to say, some critics seized on the date of bonfire night as symbolically significant, Robert Ross, for example, immediately suggesting that what these painters were up to was roughly analogous to what Guy Fawkes had planned for the Houses of Parliament, revealing the existence, as he put it, “of a widespread plot to destroy the whole fabric of European painting.” The Exhibition attracted huge publicity, and was widely denounced as being pornographic, degenerate and evil.

“It’s like meeting God without dying,” said Dorothy Parker on first encountering Orson Welles. Still in his early twenties, Welles’s fame had preceded him: the boy wonder who could read by the age of two; who could quote chunks of King Lear by the time he was seven; who had written a treatise on Nietzsche and published a best-selling book on Shakespeare before he was out of his teens. A voodoo version of Macbeth and an anti-Fascist modern-dress Julius Caesar had established his stage reputation as a stupendously original director. His sensational radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds on Halloween night in 1938 had been powerful enough to provoke mass hysteria on a scale unprecedented for the modern media, either before or since. When at the age of 25, he produced, directed, starred in and co-wrote his debut feature Citizen Kane and it turned out to have the artistry and authority of an authentic film ‘auteur’ before the term had even been invented, there seemed only one possible way Welles’s career could go: down.

“It’s like meeting God without dying,” said Dorothy Parker on first encountering Orson Welles. Still in his early twenties, Welles’s fame had preceded him: the boy wonder who could read by the age of two; who could quote chunks of King Lear by the time he was seven; who had written a treatise on Nietzsche and published a best-selling book on Shakespeare before he was out of his teens. A voodoo version of Macbeth and an anti-Fascist modern-dress Julius Caesar had established his stage reputation as a stupendously original director. His sensational radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds on Halloween night in 1938 had been powerful enough to provoke mass hysteria on a scale unprecedented for the modern media, either before or since. When at the age of 25, he produced, directed, starred in and co-wrote his debut feature Citizen Kane and it turned out to have the artistry and authority of an authentic film ‘auteur’ before the term had even been invented, there seemed only one possible way Welles’s career could go: down. Readers of this short article will be forgiven if their initial response is: “Frank who?” And if they then consult a variety of respected reference sources (e.g. Halliwell, Katz, the BFI’s screenonline website, Robert Murphy’s edited anthology of British and Irish directors, Brian McFarlane’s epic Encyclopaedia of British Cinema) they will be none the wiser, for he is not mentioned in any of them. A BFI Film Forever source cites a Frank Nesbitt who was born in Chicago in 1938 and died in 1990, but he seems to be simply the namesake of the director with whom we are concerned, who was born in South Shields on 27 June 1932 and died in Los Angeles at the age of 74. He directed three feature films in the 1960s and early 1970s whilst he was still in his thirties, but then, to the best of my knowledge, never made another film.

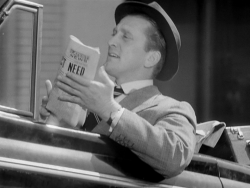

Readers of this short article will be forgiven if their initial response is: “Frank who?” And if they then consult a variety of respected reference sources (e.g. Halliwell, Katz, the BFI’s screenonline website, Robert Murphy’s edited anthology of British and Irish directors, Brian McFarlane’s epic Encyclopaedia of British Cinema) they will be none the wiser, for he is not mentioned in any of them. A BFI Film Forever source cites a Frank Nesbitt who was born in Chicago in 1938 and died in 1990, but he seems to be simply the namesake of the director with whom we are concerned, who was born in South Shields on 27 June 1932 and died in Los Angeles at the age of 74. He directed three feature films in the 1960s and early 1970s whilst he was still in his thirties, but then, to the best of my knowledge, never made another film. Plain credits on a parched, soil surface: Ace in the Hole announces itself immediately as a gritty film featuring characters with hearts of stone. The name that dominates the credits is writer/producer/director Billy Wilder; and Ace in the Hole (1951) is following on from such hard-hitting Wilder movies as Double Indemnity in 1944, The Lost Weekend in 1945 and Sunset Boulevard in 1950 which shone a harsh spotlight on unsavoury aspects of American life. Like other acclaimed writer-directors of the 1940s in Hollywood, such as Preston Sturges, John Huston and Joseph L.Mankiewicz, Wilder had become a director to protect his own scripts. ‘It isn’t important that a director knows how to write,’ he would say, ‘but it is important that he knows how to read.’

Plain credits on a parched, soil surface: Ace in the Hole announces itself immediately as a gritty film featuring characters with hearts of stone. The name that dominates the credits is writer/producer/director Billy Wilder; and Ace in the Hole (1951) is following on from such hard-hitting Wilder movies as Double Indemnity in 1944, The Lost Weekend in 1945 and Sunset Boulevard in 1950 which shone a harsh spotlight on unsavoury aspects of American life. Like other acclaimed writer-directors of the 1940s in Hollywood, such as Preston Sturges, John Huston and Joseph L.Mankiewicz, Wilder had become a director to protect his own scripts. ‘It isn’t important that a director knows how to write,’ he would say, ‘but it is important that he knows how to read.’