by NEIL SINYARD

To commemorate the 70th anniversary of the release of Carol Reed’s The Third Man and the 20th anniversary of its being voted the best British film of the century in a British Film Institute poll, I want to offer some reflections on the film and particularly on the character of Harry Lime, who, as played by Orson Welles, is assuredly one of the cinema’s most charismatic villains. A remarkable aspect of Lime’s cinematic durability is that he is only on screen for around 8 minutes or so. My focus will be on those scenes in which he appears and the reasons for their impact. To begin with, however, I wish to ruminate on one of his most striking features: his name.

To commemorate the 70th anniversary of the release of Carol Reed’s The Third Man and the 20th anniversary of its being voted the best British film of the century in a British Film Institute poll, I want to offer some reflections on the film and particularly on the character of Harry Lime, who, as played by Orson Welles, is assuredly one of the cinema’s most charismatic villains. A remarkable aspect of Lime’s cinematic durability is that he is only on screen for around 8 minutes or so. My focus will be on those scenes in which he appears and the reasons for their impact. To begin with, however, I wish to ruminate on one of his most striking features: his name.

What’s in a name?

In Ways of Escape, Graham Greene mentioned some of the symbolic interpretations which had been offered about the names of the two main characters of his screenplay, Harry Lime and Holly Martins: for example, how the former had been linked to the lime tree in Sir James Frazer’s classic study of pagan mythology, The Golden Bough (1922), and how Holly was clearly associated with Christmas, so symbolically they represented a clash between paganism and Christianity. Greene could offer a much simpler explanation for what he had in mind:

In Ways of Escape, Graham Greene mentioned some of the symbolic interpretations which had been offered about the names of the two main characters of his screenplay, Harry Lime and Holly Martins: for example, how the former had been linked to the lime tree in Sir James Frazer’s classic study of pagan mythology, The Golden Bough (1922), and how Holly was clearly associated with Christmas, so symbolically they represented a clash between paganism and Christianity. Greene could offer a much simpler explanation for what he had in mind:

The truth is I wanted for my ‘villain’ a name natural and yet disagreeable, and to me Lime represented the quicklime in which murderers were said to be buried. As for Holly, it was because my first choice of name Rollo had not met with the approval of Joseph Cotten. So much for symbols.1

However, it is worth noting that a character’s name in The Third Man, like his or her nationality, is a very slippery business in what is an extremely slippery film (in terms of its narrative development, its camera style, and even its streets, which seem to gleam with wetness although it never rains). Holly was originally Rollo but is sometimes called Harry by Anna Schmidt (Alida Valli), who is supposedly Austrian but is actually Czech, so one could surmise that Schmidt is not her real name.

However, it is worth noting that a character’s name in The Third Man, like his or her nationality, is a very slippery business in what is an extremely slippery film (in terms of its narrative development, its camera style, and even its streets, which seem to gleam with wetness although it never rains). Holly was originally Rollo but is sometimes called Harry by Anna Schmidt (Alida Valli), who is supposedly Austrian but is actually Czech, so one could surmise that Schmidt is not her real name.

Graham Greene, Ways of Escape (Penguin, 1980), pp. 181-182. ↩

“It’s like meeting God without dying,” said Dorothy Parker on first encountering Orson Welles. Still in his early twenties, Welles’s fame had preceded him: the boy wonder who could read by the age of two; who could quote chunks of King Lear by the time he was seven; who had written a treatise on Nietzsche and published a best-selling book on Shakespeare before he was out of his teens. A voodoo version of Macbeth and an anti-Fascist modern-dress Julius Caesar had established his stage reputation as a stupendously original director. His sensational radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds on Halloween night in 1938 had been powerful enough to provoke mass hysteria on a scale unprecedented for the modern media, either before or since. When at the age of 25, he produced, directed, starred in and co-wrote his debut feature Citizen Kane and it turned out to have the artistry and authority of an authentic film ‘auteur’ before the term had even been invented, there seemed only one possible way Welles’s career could go: down.

“It’s like meeting God without dying,” said Dorothy Parker on first encountering Orson Welles. Still in his early twenties, Welles’s fame had preceded him: the boy wonder who could read by the age of two; who could quote chunks of King Lear by the time he was seven; who had written a treatise on Nietzsche and published a best-selling book on Shakespeare before he was out of his teens. A voodoo version of Macbeth and an anti-Fascist modern-dress Julius Caesar had established his stage reputation as a stupendously original director. His sensational radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds on Halloween night in 1938 had been powerful enough to provoke mass hysteria on a scale unprecedented for the modern media, either before or since. When at the age of 25, he produced, directed, starred in and co-wrote his debut feature Citizen Kane and it turned out to have the artistry and authority of an authentic film ‘auteur’ before the term had even been invented, there seemed only one possible way Welles’s career could go: down. Readers of this short article will be forgiven if their initial response is: “Frank who?” And if they then consult a variety of respected reference sources (e.g. Halliwell, Katz, the BFI’s screenonline website, Robert Murphy’s edited anthology of British and Irish directors, Brian McFarlane’s epic Encyclopaedia of British Cinema) they will be none the wiser, for he is not mentioned in any of them. A BFI Film Forever source cites a Frank Nesbitt who was born in Chicago in 1938 and died in 1990, but he seems to be simply the namesake of the director with whom we are concerned, who was born in South Shields on 27 June 1932 and died in Los Angeles at the age of 74. He directed three feature films in the 1960s and early 1970s whilst he was still in his thirties, but then, to the best of my knowledge, never made another film.

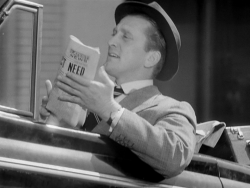

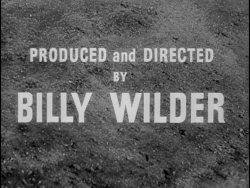

Readers of this short article will be forgiven if their initial response is: “Frank who?” And if they then consult a variety of respected reference sources (e.g. Halliwell, Katz, the BFI’s screenonline website, Robert Murphy’s edited anthology of British and Irish directors, Brian McFarlane’s epic Encyclopaedia of British Cinema) they will be none the wiser, for he is not mentioned in any of them. A BFI Film Forever source cites a Frank Nesbitt who was born in Chicago in 1938 and died in 1990, but he seems to be simply the namesake of the director with whom we are concerned, who was born in South Shields on 27 June 1932 and died in Los Angeles at the age of 74. He directed three feature films in the 1960s and early 1970s whilst he was still in his thirties, but then, to the best of my knowledge, never made another film. Plain credits on a parched, soil surface: Ace in the Hole announces itself immediately as a gritty film featuring characters with hearts of stone. The name that dominates the credits is writer/producer/director Billy Wilder; and Ace in the Hole (1951) is following on from such hard-hitting Wilder movies as Double Indemnity in 1944, The Lost Weekend in 1945 and Sunset Boulevard in 1950 which shone a harsh spotlight on unsavoury aspects of American life. Like other acclaimed writer-directors of the 1940s in Hollywood, such as Preston Sturges, John Huston and Joseph L.Mankiewicz, Wilder had become a director to protect his own scripts. ‘It isn’t important that a director knows how to write,’ he would say, ‘but it is important that he knows how to read.’

Plain credits on a parched, soil surface: Ace in the Hole announces itself immediately as a gritty film featuring characters with hearts of stone. The name that dominates the credits is writer/producer/director Billy Wilder; and Ace in the Hole (1951) is following on from such hard-hitting Wilder movies as Double Indemnity in 1944, The Lost Weekend in 1945 and Sunset Boulevard in 1950 which shone a harsh spotlight on unsavoury aspects of American life. Like other acclaimed writer-directors of the 1940s in Hollywood, such as Preston Sturges, John Huston and Joseph L.Mankiewicz, Wilder had become a director to protect his own scripts. ‘It isn’t important that a director knows how to write,’ he would say, ‘but it is important that he knows how to read.’