by NEIL SINYARD

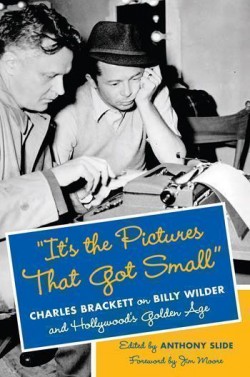

Book review: Anthony Slide (editor), “It’s the Pictures That Got Small”: Charles Brackett on Billy Wilder and Hollywood’s Golden Age (New York: Columbia University Press, December 2014), £23. 95.

After a brief spell at RKO, Charles Brackett became a staff writer then producer at Paramount from 1934 to 1949; and his journals covering that period provide a riveting perspective on the daily routine of a Hollywood studio in its prime. Brackett also became half of the most celebrated screenwriting partnership in Hollywood history. In just over ten years he and Billy Wilder collaborated on thirteen screenplays, most of them critical and commercial successes, some of them enduring classics of the screen. They wrote two of the greatest screen comedies of the late 1930s, Midnight for Mitchell Leisen and Ninotchka for Ernst Lubitsch (both 1939). After scripting Ball of Fire (1941) for Howard Hawks, they became a producer-director as well as writing team, with Brackett as producer and Wilder as director; and proceeded to make audacious trailblazing dramas such as The Lost Weekend (1945) and Sunset Boulevard (1950). As most film buffs will know, the title of this book is a famous line from Sunset Boulevard, when William Holden’s down-at-heel screenwriter has recognised a former star of the silent screen, Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) and said: ‘You used to be big.’ ‘I am big,’ she has retorted imperiously, ‘It’s the pictures that got small.’ Less well known is the fact that it was Charles Brackett who was savvy enough to see the importance of that moment and recommend that the line be re-shot in close-up, probably also sensing how it foretold the devastating final close-up of that magnificent film.